Next: Observation log for June-July Up: thesis Previous: Summary Contents

|

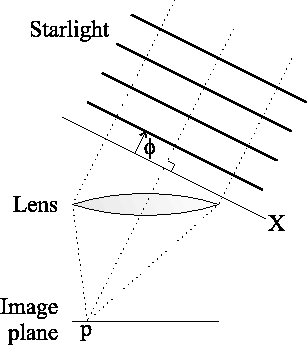

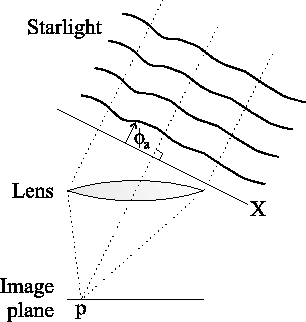

Figure A.2 shows the same situation as

Figure A.1, but the incoming wavefronts have been

perturbed by the atmosphere. The phase fluctuations will affect the

integral of the wavefunction over plane ![]() altering the measured

intensity at point

altering the measured

intensity at point ![]() .

.

|

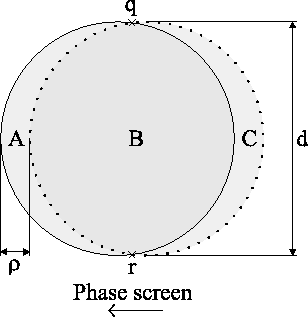

For the case of a single wind-blown Taylor screen, the phase

perturbations introduced by the atmosphere will be translated

laterally across the telescope aperture by the wind with no change in

the structure of these perturbations. The modulus of the integral of

the wavefunction over the plane ![]() is not directly affected by the

lateral motion of the phase fluctuations, but the motion of the screen

introduces new phase perturbations at the upwind side of the aperture

and removes phase perturbations at the downwind side. This can be seen

clearly if the outline of the telescope aperture is projected along

the line of sight from

is not directly affected by the

lateral motion of the phase fluctuations, but the motion of the screen

introduces new phase perturbations at the upwind side of the aperture

and removes phase perturbations at the downwind side. This can be seen

clearly if the outline of the telescope aperture is projected along

the line of sight from ![]() onto the Taylor screen, as shown by the

solid circle in Figure A.3. After time has elapsed

and the wind-blown Taylor screen has moved a distance

onto the Taylor screen, as shown by the

solid circle in Figure A.3. After time has elapsed

and the wind-blown Taylor screen has moved a distance ![]() , the

outline of telescope aperture will be projected onto the dotted

circle. Area

, the

outline of telescope aperture will be projected onto the dotted

circle. Area ![]() is common to both timepoints and will contribute

equally to the amplitude of the wavefunction at point

is common to both timepoints and will contribute

equally to the amplitude of the wavefunction at point ![]() in the image

plane, but the contribution from area

in the image

plane, but the contribution from area ![]() will be lost, and a new

contribution from area

will be lost, and a new

contribution from area ![]() will be included at the later timepoint. In

reality, the atmospheric phase in areas

will be included at the later timepoint. In

reality, the atmospheric phase in areas ![]() and

and ![]() will remain

correlated to that in area

will remain

correlated to that in area ![]() over a region extending approximately

over a region extending approximately

![]() from the boundary of area

from the boundary of area ![]() , but for the particular case of

large diameter apertures this only has a small effect on our

calculations and will be neglected in this simple approximation.

, but for the particular case of

large diameter apertures this only has a small effect on our

calculations and will be neglected in this simple approximation.

|

We can write the contributions ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() to the wavefunction at point

to the wavefunction at point ![]() from areas

from areas ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() respectively as:

respectively as:

where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() describe the amplitudes

and

describe the amplitudes

and ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() the phases of these

contributions. If the linear dimensions of areas

the phases of these

contributions. If the linear dimensions of areas ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() in

Figure A.3 are much larger than

in

Figure A.3 are much larger than ![]() , then the

phases

, then the

phases ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() will not be correlated

with each other, as the structure function of

Equation 1.3 indicates that the typical phase

variation between points separated by distances much greater

will not be correlated

with each other, as the structure function of

Equation 1.3 indicates that the typical phase

variation between points separated by distances much greater ![]() will be many cycles in magnitude.

will be many cycles in magnitude.

If the linear dimensions of areas ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are much larger

than

are much larger

than ![]() then the ensemble average amplitudes

then the ensemble average amplitudes

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() will be

proportional to the square root of the areas of

will be

proportional to the square root of the areas of ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. This can most clearly be seen if we imagine utilising a

telescope whose aperture has the same size and shape as one of these

three regions. The atmospheric seeing will generate an image with a

FWHM of approximately

respectively. This can most clearly be seen if we imagine utilising a

telescope whose aperture has the same size and shape as one of these

three regions. The atmospheric seeing will generate an image with a

FWHM of approximately ![]() regardless of the aperture size

and shape (as long as the aperture is much larger than

regardless of the aperture size

and shape (as long as the aperture is much larger than ![]() ), with

an average intensity proportional to the area of the aperture.

), with

an average intensity proportional to the area of the aperture.

As the phases ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are not

correlated with each other, if the light from more than one of the

these regions is combined then the ensemble averages of the relevant

amplitudes must be added in quadrature to give the total amplitude. It

is useful to consider three ensemble average intensities

are not

correlated with each other, if the light from more than one of the

these regions is combined then the ensemble averages of the relevant

amplitudes must be added in quadrature to give the total amplitude. It

is useful to consider three ensemble average intensities

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() which describe the contributions from the areas

which describe the contributions from the areas ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() as

follows:

as

follows:

| (A.4) | |||

| (A.5) | |||

| (A.6) |

| (A.7) |

We are interested in the intensity ![]() produced at the first

timepoint when light from areas

produced at the first

timepoint when light from areas ![]() and

and ![]() is combined:

is combined:

| (A.8) |

| (A.9) |

| (A.10) | |||

| (A.11) |

The value of

![]() is directly dependent on

is directly dependent on

![]() . For non-zero values of

. For non-zero values of

![]() , the

fluctuations in the instantaneous intensities

, the

fluctuations in the instantaneous intensities ![]() and

and ![]() will be correlated, as both intensities include a contribution from

will be correlated, as both intensities include a contribution from

![]() . Conversely, if the value of

. Conversely, if the value of

![]() were

zero then the contribution

were

zero then the contribution ![]() would be zero, and fluctuations

in

would be zero, and fluctuations

in ![]() and

and ![]() would be completely uncorrelated. We are

interested in determining the size of the contribution

would be completely uncorrelated. We are

interested in determining the size of the contribution

![]() for which the correlation between fluctuations in

for which the correlation between fluctuations in ![]() and

and ![]() has dropped by a factor of

has dropped by a factor of ![]() . As the wavefront

components

. As the wavefront

components ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() are uncorrelated

Rayleigh distributions, this will be true when the ensemble average

intensity

are uncorrelated

Rayleigh distributions, this will be true when the ensemble average

intensity

![]() from area

from area ![]() contributes

contributes

![]() of the total intensity:

of the total intensity:

The intensity

![]() will obey

Equation A.12 when areas

will obey

Equation A.12 when areas ![]() and

and ![]() are related as

follows:

are related as

follows:

| (A.13) |

If the telescope aperture is described by a function

![]() such as the example case in

Equation 1.7, then area of overlap

such as the example case in

Equation 1.7, then area of overlap ![]() between two offset apertures comes directly from the autocorrelation of

this function

between two offset apertures comes directly from the autocorrelation of

this function

![]() :

:

| (A.14) |

For the simple case presented in Figure A.3 of a

filled circular aperture of diameter ![]() , the area of overlap

, the area of overlap ![]() can

be calculated geometrically. The line joining

can

be calculated geometrically. The line joining ![]() and

and ![]() in

Figure A.3 is a chord to both the dotted and filled

circles.

in

Figure A.3 is a chord to both the dotted and filled

circles. ![]() is constructed from two symmetric regions either side of

this chord, each having an area:

is constructed from two symmetric regions either side of

this chord, each having an area: