Next: Conclusions Up: Charge transfer efficiency problems Previous: Charge transfer efficiency problems Contents

Short exposure images were taken of a camera ``test card'' transparency using standard slide-copying optics, with a CCD65 detector in the camera. The voltage settings on the camera were such that the charge transfer efficiency deviated significantly from unity at low signal levels. At high signal levels the images of the test card showed a high degree of fine structure, ideal for charge transfer efficiency measurements.

Datasets of ![]() images each were taken operating the CCD65 at high

multiplication register gain with exposure times of

images each were taken operating the CCD65 at high

multiplication register gain with exposure times of ![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() . In the test card images these light levels corresponded to

. In the test card images these light levels corresponded to

![]() --

--![]() photons per pixel per frame and

photons per pixel per frame and ![]() --

--![]() photons per

pixel per frame respectively. Ten exposures of

photons per

pixel per frame respectively. Ten exposures of ![]()

![]() were also

taken with no multiplication register gain to provide an accurate

representation of the test card at high signal level. There was no

evidence for charge transfer efficiency problems in these long exposure

images.

were also

taken with no multiplication register gain to provide an accurate

representation of the test card at high signal level. There was no

evidence for charge transfer efficiency problems in these long exposure

images.

The raw images did not show any visual evidence for poor charge

transfer efficiency, but the signal level was too low in the

individual ![]()

![]() exposures to make an accurate

assessment. Software was written by the author to combine the short

exposures and deconvolve the resulting images in order to make a

quantitive assessment of the charge transfer efficiency.

exposures to make an accurate

assessment. Software was written by the author to combine the short

exposures and deconvolve the resulting images in order to make a

quantitive assessment of the charge transfer efficiency.

The ![]()

![]() exposures were co-added to increase the signal-to-noise,

as were the

exposures were co-added to increase the signal-to-noise,

as were the ![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]() exposures. The summed images from

the

exposures. The summed images from

the ![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]() exposures were then deconvolved using the

summed image from the long exposures in order to give a ``PSF'' which

described the charge transfer efficiency problems at low light

levels. The fraction of the signal residing a given number of pixels

from the origin of this PSF corresponds to the fraction of electrons

which have been displaced by this distance due to charge transfer

efficiency problems. In order to control the noise in the

deconvolution process, a 2-D version of the Nahman-Guillaume one

parameter filter was used (Nahman & Guillaume, 1981). The filter parameter was

adjusted until there was good dynamic range between the central peak

of the PSF and the noise floor in the wings. In order to confirm that

the filter was not adversely affecting the shape of the PSF, different

long exposure images were deconvolved in the same way, providing a

strongly peaked response at the origin which dropped to the noise

floor within two pixels of the origin.

exposures were then deconvolved using the

summed image from the long exposures in order to give a ``PSF'' which

described the charge transfer efficiency problems at low light

levels. The fraction of the signal residing a given number of pixels

from the origin of this PSF corresponds to the fraction of electrons

which have been displaced by this distance due to charge transfer

efficiency problems. In order to control the noise in the

deconvolution process, a 2-D version of the Nahman-Guillaume one

parameter filter was used (Nahman & Guillaume, 1981). The filter parameter was

adjusted until there was good dynamic range between the central peak

of the PSF and the noise floor in the wings. In order to confirm that

the filter was not adversely affecting the shape of the PSF, different

long exposure images were deconvolved in the same way, providing a

strongly peaked response at the origin which dropped to the noise

floor within two pixels of the origin.

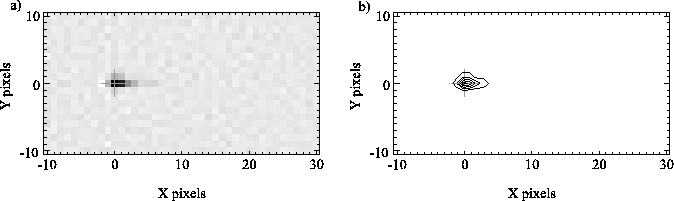

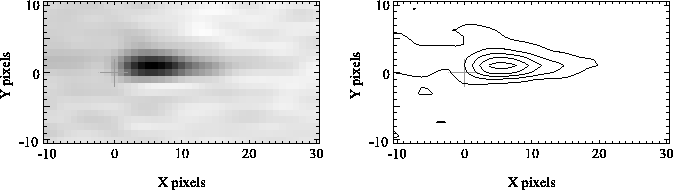

Figure 4.10 shows the result of deconvolving a section of the

summed image from the ![]()

![]() exposures. The PSF shows a strong peak

at the origin corresponding to those electrons which were transferred

with good charge transfer efficiency. Weak tails extend both to the

right and upwards, indicating that some of the photo-electrons are

experiencing much poorer charge transfer efficiency for either

horizontal or vertical transfers. With the shorter exposures (having

fewer photons per pixel), the strong peak at the origin disappears,

and the tails to the right and in the upwards direction are broadened

and strongly enhanced to form a single peak offset from the origin, as

shown by Figure 4.11.

exposures. The PSF shows a strong peak

at the origin corresponding to those electrons which were transferred

with good charge transfer efficiency. Weak tails extend both to the

right and upwards, indicating that some of the photo-electrons are

experiencing much poorer charge transfer efficiency for either

horizontal or vertical transfers. With the shorter exposures (having

fewer photons per pixel), the strong peak at the origin disappears,

and the tails to the right and in the upwards direction are broadened

and strongly enhanced to form a single peak offset from the origin, as

shown by Figure 4.11.

|

|

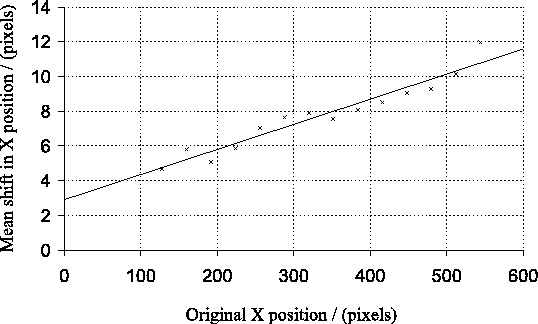

A PSF was calculated in this way for different regions of the test

card image using the ![]()

![]() exposures. The horizontal offset and

vertical offset of the peak in the PSF was found to depend linearly

on the horizontal position and vertical position respectively in the

image. This is consistent with charge transfer efficiency problems in

the image and store areas of the CCD, as electrons which are generated

further from the readout register must undergo a larger number of

transfers.

exposures. The horizontal offset and

vertical offset of the peak in the PSF was found to depend linearly

on the horizontal position and vertical position respectively in the

image. This is consistent with charge transfer efficiency problems in

the image and store areas of the CCD, as electrons which are generated

further from the readout register must undergo a larger number of

transfers.

Figure 4.12 shows a plot of the horizontal offset in the PSF

peak against the horizontal (``![]() '') position of the region used for

the calculations. The data points are fit by a line which crosses the

'') position of the region used for

the calculations. The data points are fit by a line which crosses the

![]() -axis at an

-axis at an ![]() value of

value of ![]() . This implies that a significant

fraction of the charge transfer efficiency loss is occurring after the

signal has left the image and store areas of the CCD, and is

presumably occurring in the multiplication register. The bulk of the

charge transfer efficiency losses do seem to occur in horizontal

(serial) transfers in the store area of the CCD, however. The gradient

of the line in Figure 4.12 indicates that electrons are being

``left behind'' in

. This implies that a significant

fraction of the charge transfer efficiency loss is occurring after the

signal has left the image and store areas of the CCD, and is

presumably occurring in the multiplication register. The bulk of the

charge transfer efficiency losses do seem to occur in horizontal

(serial) transfers in the store area of the CCD, however. The gradient

of the line in Figure 4.12 indicates that electrons are being

``left behind'' in ![]() of the serial transfers in the store area

of the CCD for these measurements.

of the serial transfers in the store area

of the CCD for these measurements.

|

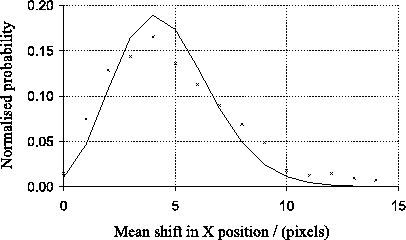

A cross section through the PSF calculated for a region centred on

![]() pixels is shown in Figure 4.13. The curve is

similar in shape to the binomial distribution which would be expected

if it was the result of

pixels is shown in Figure 4.13. The curve is

similar in shape to the binomial distribution which would be expected

if it was the result of ![]() transfers attempts, each having a

transfers attempts, each having a

![]() chance of failing to transfer the electron.

chance of failing to transfer the electron.

|

The charge transfer efficiency was found to be strongly dependent on the (variable) operating voltages and environmental conditions of the camera. It was possible to get very good charge transfer efficiency in the laboratory with the CCD87 by selecting appropriate operating conditions. The operating voltages used during observations at the NOT are not precisely known, and for this reason it will not be possible to predict the charge transfer efficiency which was present for observations at the NOT.

The experimental measurements and calculations of charge transfer efficiency at low signal level are currently relatively time consuming, and require an image with suitably fine structure to be projected on to the CCD in a stable experimental setup. It would be extremely beneficial if an automated approach to this analysis could be developed which could be performed when the camera was at an astronomical telescope, so that the charge transfer efficiency could be maximised before astronomical observations began.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14