Next: Short exposure optical imaging Up: Introduction Previous: Introduction Contents

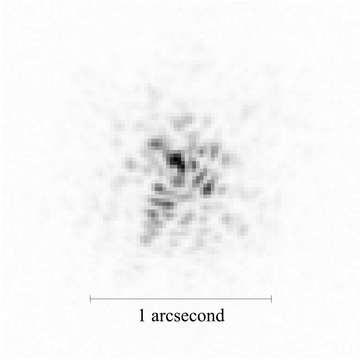

For much of the 20th Century, the blurring effect of the atmosphere

(known as atmospheric ``seeing'') limited the resolution available to

optical astronomers. This degradation in image quality results from

fluctuations in the refractive index of air as a function of position

above the telescope. The image of an unresolved (i.e. essentially

point-like) star is turned into a dancing pattern of ``speckles''. An

example short exposure image from such a pattern is shown in

Figure 1.1. In order to obtain better

atmospheric seeing conditions, telescopes were constructed at high

altitudes on sites where the air above the telescope was particularly

stable. Even at the best observatory sites the atmospheric seeing

conditions typically limit the resolution which can be achieved with

conventional astronomical imaging to about ![]()

![]() (

(![]()

![]() ) at visible wavelengths.

) at visible wavelengths.

|

Studies of short exposure images obtained through atmospheric seeing by Antoine Labeyrie in 1970 (Labeyrie, 1970) indicated that information about the high resolution structure of an astronomical object could be obtained from these short exposures despite the perturbing influence of the atmosphere. A number of imaging techniques were developed based on his approach, most involving fast frame-rate cameras (essentially high performance motion picture or video cameras) situated at the telescope focus. This thesis discusses one of these techniques in detail, that of Lucky Exposures . The Lucky Exposures method was first discussed in depth by David Fried in 1978 (Fried, 1978), and the first experimental results followed in the 1980s. The optimum performance for the technique was not achieved during those observations, partly due to the camera equipment available at the time and partly due to the approach used for the data analysis. This thesis presents more recent results which demonstrate the enormous potential of the technique.

The effects of atmospheric seeing are qualitatively similar throughout

the visible and near infra-red wavebands. At large telescopes the long

exposure image resolution is generally slightly higher at longer

wavelengths, and the timescale for the changes in the dancing speckle

patterns is substantially lower. This would argue for the use of long

wavelengths in experimental studies of these speckle patterns

(although short wavelengths are of equal astronomical interest). The

high cost of sensitive imaging detectors which operate at wavelengths

longer than ![]()

![]() makes them less appealing for studies of

imaging performance, so the results presented in later chapters of

this thesis will be restricted to wavelengths shorter than

makes them less appealing for studies of

imaging performance, so the results presented in later chapters of

this thesis will be restricted to wavelengths shorter than ![]()

![]() . The cameras used for my work are sufficiently fast to

accurately sample the atmosphere at the wavelengths used. The

approaches developed in this thesis could equally be applied to longer

wavelengths given suitable detectors and telescopes, broadening the

astronomical potential of the method substantially.

. The cameras used for my work are sufficiently fast to

accurately sample the atmosphere at the wavelengths used. The

approaches developed in this thesis could equally be applied to longer

wavelengths given suitable detectors and telescopes, broadening the

astronomical potential of the method substantially.