Next: Results with binary stars Up: Observational results with single Previous: Temporal properties of the Contents

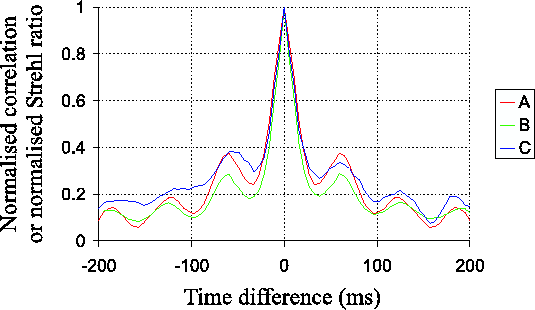

The Strehl ratio for the shift-and-add image using all the exposures

is plotted as a function of this time difference in curve B

of Figure 3.18, alongside curve A,

the temporal autocorrelation of the speckle pattern previously shown

in Figures 3.16 and

3.17. Qualitatively the curves appear similar

suggesting that the decorrelation process is not substantially

different for the brightest speckle than for the fixed point chosen in

the image plane. Both curves are almost equally affected by the

telescope oscillation as would be expected. If we ignore the effects

of the telescope oscillation, the brightest speckle does appear to

decorrelate slightly more quickly at first than the autocorrelation

curve for the measurements taken at a fixed location in the

image. Also shown in the Figure are the Strehl ratios obtained in the

final image when the best ![]() % of exposures are used, based upon the

Strehl ratio and position of the brightest speckle measured in a

different short exposure in the same run (i.e. taken at a slightly

different time). If we ignore the effects of the telescope

oscillation, this appears to decay slightly more slowly than the other

timescales, perhaps indicating that the atmospheric coherence time is

slightly extended during the times of the best exposures. This is a

small effect, and it is clear that the timescales for the decay of the

brightest speckle are very close to the coherence timescale of the

speckle pattern.

% of exposures are used, based upon the

Strehl ratio and position of the brightest speckle measured in a

different short exposure in the same run (i.e. taken at a slightly

different time). If we ignore the effects of the telescope

oscillation, this appears to decay slightly more slowly than the other

timescales, perhaps indicating that the atmospheric coherence time is

slightly extended during the times of the best exposures. This is a

small effect, and it is clear that the timescales for the decay of the

brightest speckle are very close to the coherence timescale of the

speckle pattern.

|

Figure 3.18 shows that the timescale for the

decay of the brightest speckle is ![]() --

--![]()

![]() brought about

predominantly by the

brought about

predominantly by the ![]()

![]() telescope oscillation. If exposure

times greater than this are used, one would expect the typical Strehl

ratios of the exposures to be reduced. This was tested experimentally

by splitting the dataset on

telescope oscillation. If exposure

times greater than this are used, one would expect the typical Strehl

ratios of the exposures to be reduced. This was tested experimentally

by splitting the dataset on ![]() Aquilae into groups of five

consecutive exposures. The five exposures in each group were added

together without re-centring to form a single exposure with five times

the duration. The best

Aquilae into groups of five

consecutive exposures. The five exposures in each group were added

together without re-centring to form a single exposure with five times

the duration. The best ![]() % of these

% of these ![]()

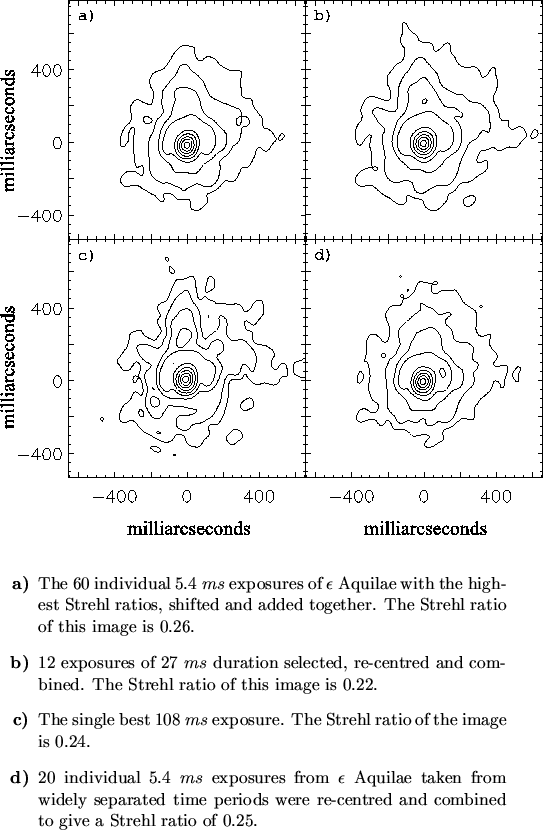

![]() exposures is shown as

a contour plot in Figure 3.19b alongside the

shift-and-add image from the best

exposures is shown as

a contour plot in Figure 3.19b alongside the

shift-and-add image from the best ![]() % of the original

% of the original ![]()

![]() exposures in Figure 3.19a. The increase in exposure time

from

exposures in Figure 3.19a. The increase in exposure time

from ![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]() brings about a reduction in the Strehl

ratio of the best

brings about a reduction in the Strehl

ratio of the best ![]() % from

% from ![]() for Figure 3.19a to

for Figure 3.19a to

![]() for Figure 3.19b. The image FWHM is increased

from

for Figure 3.19b. The image FWHM is increased

from ![]()

![]() to

to ![]()

![]() . It is clear that the

amplitude of the telescope oscillation is small enough that relative

good image quality can still be obtained with exposure times as long

as

. It is clear that the

amplitude of the telescope oscillation is small enough that relative

good image quality can still be obtained with exposure times as long

as ![]()

![]() using the Lucky Exposures method.

using the Lucky Exposures method.

|

Figure 3.19c shows the single best ![]()

![]() exposure

formed by summing together without re-centring

exposure

formed by summing together without re-centring ![]() consecutive short

exposures from the run on

consecutive short

exposures from the run on ![]() Aquilae. The Strehl ratio for

this image is

Aquilae. The Strehl ratio for

this image is ![]() . The small amplitude of the telescope oscillation

seen in movies generated from the raw short exposures around the

moment that the

. The small amplitude of the telescope oscillation

seen in movies generated from the raw short exposures around the

moment that the ![]() constituent short exposures were taken may partly

explain the high Strehl ratio obtained. It is clear that the

atmospheric timescale must have been quite long at the time this

exposure was taken. Although the Strehl ratios are comparable, the

shift-and-add images shown in Figures 3.19a and

3.19b show much less structure in the wings of the PSF

than the single exposure of Figure 3.19c. This is

probably due to the shift-and-add images being the average of many

atmospheric realisations, which helps to smooth out the fluctuations

in the wings of the PSF. To demonstrate that this is not simply an

integration-time effect, Figure 3.19d shows a

shift-and-add image with the same total integration time and similar

Strehl ratio (

constituent short exposures were taken may partly

explain the high Strehl ratio obtained. It is clear that the

atmospheric timescale must have been quite long at the time this

exposure was taken. Although the Strehl ratios are comparable, the

shift-and-add images shown in Figures 3.19a and

3.19b show much less structure in the wings of the PSF

than the single exposure of Figure 3.19c. This is

probably due to the shift-and-add images being the average of many

atmospheric realisations, which helps to smooth out the fluctuations

in the wings of the PSF. To demonstrate that this is not simply an

integration-time effect, Figure 3.19d shows a

shift-and-add image with the same total integration time and similar

Strehl ratio (![]() ) to Figure 3.19c, but using

individual short exposures taken at widely separated times. The wings

of the PSF are substantially smoother than for the

) to Figure 3.19c, but using

individual short exposures taken at widely separated times. The wings

of the PSF are substantially smoother than for the ![]()

![]() single

exposure of Figure 3.19c. This suggests that a

significant fraction of the noise in these images results from the

limited number of atmospheric realisations used in generating them.

single

exposure of Figure 3.19c. This suggests that a

significant fraction of the noise in these images results from the

limited number of atmospheric realisations used in generating them.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14