Next: Timescales for exposure selection Up: Observational results with single Previous: Exposure selection results Contents

In order to minimise the effects of long-timescale drift in the

location of the stellar PSF on the measurements, the pixel located at

the centroid of the long exposure average image of the run on

![]() Aquilae was selected (i.e. the centroid of

Figure 3.14d). The average image for this run had an

unusually compact PSF, showing no evidence for substantial drift in

the location of the speckle pattern during the

Aquilae was selected (i.e. the centroid of

Figure 3.14d). The average image for this run had an

unusually compact PSF, showing no evidence for substantial drift in

the location of the speckle pattern during the ![]()

![]() run. The

stellar flux from the selected pixel was recorded in each short

exposure, producing a one-dimensional dataset characterising the

temporal fluctuations in the PSF. The temporal power spectrum of this

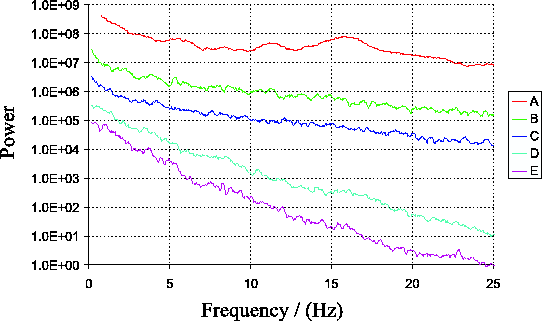

dataset is shown as curve A in Figure 3.15. The

power spectrum shows a peak at a frequency of

run. The

stellar flux from the selected pixel was recorded in each short

exposure, producing a one-dimensional dataset characterising the

temporal fluctuations in the PSF. The temporal power spectrum of this

dataset is shown as curve A in Figure 3.15. The

power spectrum shows a peak at a frequency of ![]()

![]() . This is in

close agreement with the first harmonic of mechanical oscillation for

the telescope structure, and movies made from the raw speckle images

clearly show motion consistent with such oscillations. The frequency

was confirmed to be

. This is in

close agreement with the first harmonic of mechanical oscillation for

the telescope structure, and movies made from the raw speckle images

clearly show motion consistent with such oscillations. The frequency

was confirmed to be ![]()

![]() by measuring the position of the

brightest speckle in each short exposure and then looking at the

temporal power spectrum of this time series.

by measuring the position of the

brightest speckle in each short exposure and then looking at the

temporal power spectrum of this time series.

|

The effect of telescope oscillation on the temporal fluctuations at a

fixed point in the image plane can be seen by splitting into partial

derivatives the derivative of the flux ![]() with respect to time at a

fixed point in the telescope image plane. It is simplest to work in a

coordinate frame which is fixed with respect to the speckle pattern,

and study the effect of moving the optical detector at a velocity

with respect to time at a

fixed point in the telescope image plane. It is simplest to work in a

coordinate frame which is fixed with respect to the speckle pattern,

and study the effect of moving the optical detector at a velocity

![]() relative to the speckle pattern. In these coordinates,

the time derivative of the flux is:

relative to the speckle pattern. In these coordinates,

the time derivative of the flux is:

It is the total differential from

Equation 3.3 which limits the exposure time

we can use during observations at the NOT. For our data it is the

telescope oscillation which provides the dominant contribution on

short timescales. If the amplitude of the telescope oscillation could

somehow be reduced however, the ultimate limit to the exposure time

would be set by the partial derivative

![]() . This term represents the component of the

time variation in the flux which is introduced directly by changes in

the speckle pattern. It is of interest to try to measure the timescale

associated with this, as it would be applicable to other telescopes

operating under similar atmospheric conditions.

. This term represents the component of the

time variation in the flux which is introduced directly by changes in

the speckle pattern. It is of interest to try to measure the timescale

associated with this, as it would be applicable to other telescopes

operating under similar atmospheric conditions.

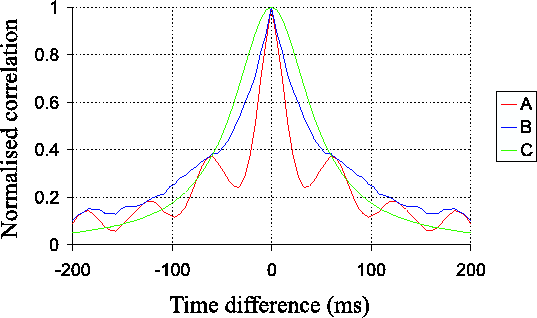

Curve A in Figure 3.16 shows the temporal

autocorrelation of the same dataset from ![]() Aquilae as

Figure 3.15 (it represents the Fourier transform

of curve A in Figure 3.15). The curve has been

normalised so that it ranges from unity at zero time difference to a

mean value of zero for time differences between

Aquilae as

Figure 3.15 (it represents the Fourier transform

of curve A in Figure 3.15). The curve has been

normalised so that it ranges from unity at zero time difference to a

mean value of zero for time differences between ![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() . The

. The ![]()

![]() oscillatory component is clearly

visible. This oscillation is largely responsible for the initial

decorrelation in the measured flux as a function of time. The

telescope oscillation will only reduce the temporal correlation, so

the true autocorrelation function corresponding to the atmosphere

would lie above curve A for all time differences. The effect of

photon-shot noise was negligible in these observations due to the high

flux in each individual exposure. The frame rate (

oscillatory component is clearly

visible. This oscillation is largely responsible for the initial

decorrelation in the measured flux as a function of time. The

telescope oscillation will only reduce the temporal correlation, so

the true autocorrelation function corresponding to the atmosphere

would lie above curve A for all time differences. The effect of

photon-shot noise was negligible in these observations due to the high

flux in each individual exposure. The frame rate (![]()

![]() ) was

sufficiently high that the sharp peak in curve A around zero time

difference is relatively well sampled in this dataset (the peak does

not simply correspond to a single high value at zero time difference,

but contains several data points).

) was

sufficiently high that the sharp peak in curve A around zero time

difference is relatively well sampled in this dataset (the peak does

not simply correspond to a single high value at zero time difference,

but contains several data points).

|

Curve B in this Figure is a function extrapolated from the measured

curve by dividing it by a decaying sinusoid having the same period as

the telescope oscillation. The amplitude and decay time of the

sinusoid were chosen so as to minimise the residual component at

![]()

![]() . This curve is intended to represent a possible shape for

the temporal autocorrelation in the absence of telescope oscillation.

. This curve is intended to represent a possible shape for

the temporal autocorrelation in the absence of telescope oscillation.

Curve C shows a fit to curve B of the form of Equation 2.2 (based on the model of temporal fluctuations by Aime et al. (1986)). The broad peak produced by this model does not seem consistent with the sharp peak seen in the experimental data.

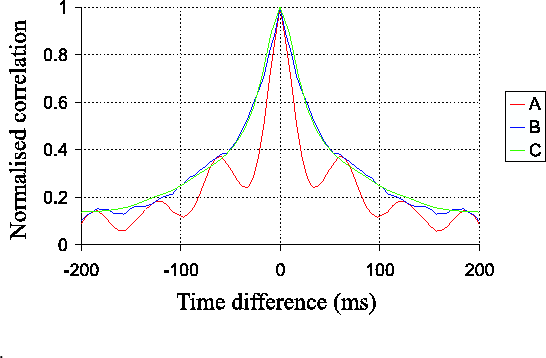

The sharp peak seen in curves A and B of

Figure 3.16 could be reproduced qualitatively

in numerical simulations if multiple Taylor screens were used with a

scatter of different wind velocities. One example of a simulation

which gave a better fit to the shape of the experimentally measured

temporal autocorrelation is shown as curve C in

Figure 3.17. The atmospheric model for this

simulation consisted of two Taylor screens moving at constant

velocities. Both layers moved in the same direction but with different

speeds. One layer, containing ![]() of the the turbulence took

of the the turbulence took

![]()

![]() to cross the diameter of the telescope aperture. The other

contained

to cross the diameter of the telescope aperture. The other

contained ![]() of the turbulence, but took only

of the turbulence, but took only ![]()

![]() to cross

the telescope aperture. Curves A and B from

Figure 3.16 are also reproduced as curves

A and B in Figure 3.17 for

comparison. Temporal power spectra generated using this model of the

atmosphere are plotted as curves B and C in

Figure 3.15. It is clear that they provide a much

better fit to the experimentally measured data in curve A

than the single layer atmospheric models shown in curves

D and E.

to cross

the telescope aperture. Curves A and B from

Figure 3.16 are also reproduced as curves

A and B in Figure 3.17 for

comparison. Temporal power spectra generated using this model of the

atmosphere are plotted as curves B and C in

Figure 3.15. It is clear that they provide a much

better fit to the experimentally measured data in curve A

than the single layer atmospheric models shown in curves

D and E.

|

It is clear from the temporal autocorrelation plots of

Figures 3.16 and 3.17 that

there are (at least) two timescales associated with the decorrelation

of the speckle pattern: the half-period of the telescope oscillation

and the timescale for the decorrelation of the atmosphere. The

decorrelation timescale ![]() (as defined in

Chapter 2.2.1) which results from the combination

of these two effects is

(as defined in

Chapter 2.2.1) which results from the combination

of these two effects is ![]()

![]() . Using a simple fit to the

oscillatory component (used to produce curve B in both

Figures) the decorrelation timescale for the atmosphere alone was

calculated to be

. Using a simple fit to the

oscillatory component (used to produce curve B in both

Figures) the decorrelation timescale for the atmosphere alone was

calculated to be ![]()

![]() .

.

If the atmosphere had a single, boiling-free layer then

Equation 2.14 could be used to obtain the wind

velocity. Taking ![]()

![]() (consistent with the seeing disk,

and with the Strehl ratios in

Figure 3.10), a wind velocity of

(consistent with the seeing disk,

and with the Strehl ratios in

Figure 3.10), a wind velocity of

![]()

![]()

![]() is obtained. This is significantly larger than the

wind velocity near ground level of

is obtained. This is significantly larger than the

wind velocity near ground level of ![]()

![]()

![]() (from

Figure 3.7), but would not be implausible if the

turbulence were situated at high altitude.

(from

Figure 3.7), but would not be implausible if the

turbulence were situated at high altitude.

If the atmosphere had multiple layers travelling at different

velocities, and the timescale for decorrelation of the wavefronts was

shorter than the wind crossing timescale of the telescope aperture,

then the dispersion in the wind velocities ![]() could be

calculated using

Equation 2.12. The value obtained for

could be

calculated using

Equation 2.12. The value obtained for

![]()

![]() is

is ![]()

![]()

![]() (again

taking

(again

taking ![]()

![]() ). This level of dispersion in wind velocities

between atmospheric layers seems consistent with the wind

velocity of

). This level of dispersion in wind velocities

between atmospheric layers seems consistent with the wind

velocity of ![]()

![]()

![]() measured near to the ground.

measured near to the ground.

Both of these atmospheric configurations are plausible. The second is perhaps more likely given that the strongest turbulence is most commonly found at relatively low altitudes, where small wind speeds were observed.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14