Simulations of the CCD65 L3Vision device with  gain stages were

first undertaken using model 1 for the individual gain stages (where

the additional impact ionisation electrons were chosen from a Poisson

distribution). In the simulations the same value of the gain

gain stages were

first undertaken using model 1 for the individual gain stages (where

the additional impact ionisation electrons were chosen from a Poisson

distribution). In the simulations the same value of the gain  was

used for each of the

was

used for each of the  stages. The total gain of the

multiplication register was thus given by

stages. The total gain of the

multiplication register was thus given by  . The three

simulations used three different values of

. The three

simulations used three different values of  chosen to give total

multiplication register gains

chosen to give total

multiplication register gains  of

of  ,

,  and

and

. The probability distributions for the output electrons in

these three simulations are shown in

Figure 4.2.

. The probability distributions for the output electrons in

these three simulations are shown in

Figure 4.2.

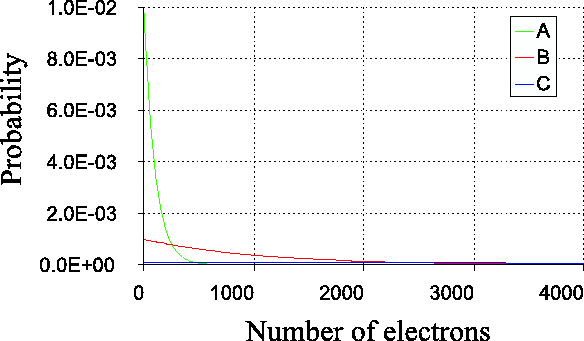

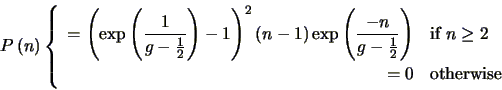

Figure 4.2:

The probability distribution for the number of output electrons from a

multiplication register of  stages with a single electron input

and total register gains of

stages with a single electron input

and total register gains of  ,

,  and

and  (curves A, B and

C respectively). All three probability curves fall to zero for the

case of less than one output electron. For these simulations model 1

was used for the individual gain stages, where additional electrons

are selected from a Poisson distribution. The same data are plotted on

a logarithmic scale in Figure 4.3.

(curves A, B and

C respectively). All three probability curves fall to zero for the

case of less than one output electron. For these simulations model 1

was used for the individual gain stages, where additional electrons

are selected from a Poisson distribution. The same data are plotted on

a logarithmic scale in Figure 4.3.

|

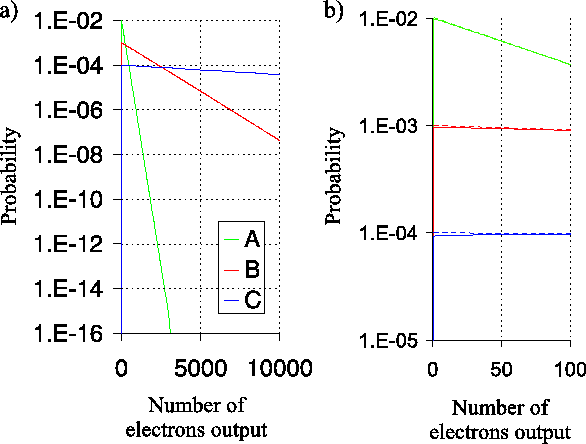

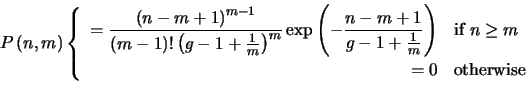

The probability distributions for the output electrons are well

approximated by decaying exponential curves for large values of

. This is highlighted in Figure 4.3a

where the curves are plotted on a logarithmic scale. The probability

curves appear as straight lines over a wide range of

. This is highlighted in Figure 4.3a

where the curves are plotted on a logarithmic scale. The probability

curves appear as straight lines over a wide range of  in the

plot. For very large values of

in the

plot. For very large values of  the probability reaches the

computational accuracy of the software corresponding to a value of

the probability reaches the

computational accuracy of the software corresponding to a value of

, and beyond this point the probability calculations are

dominated by noise. Figure 4.3b shows an

expanded view of the probability distributions for small

, and beyond this point the probability calculations are

dominated by noise. Figure 4.3b shows an

expanded view of the probability distributions for small

. Exponential curves were least-squares fitted to the probability

curves for the large

. Exponential curves were least-squares fitted to the probability

curves for the large  region, and these are extrapolated as dashed

curves in this plot. For small values of

region, and these are extrapolated as dashed

curves in this plot. For small values of  (

( ) the

probability curve begins to fall very slightly below the best fit

exponential before dropping rapidly to zero for

) the

probability curve begins to fall very slightly below the best fit

exponential before dropping rapidly to zero for  .

.

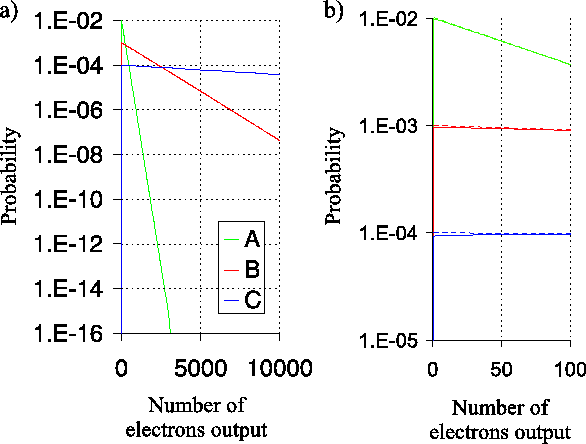

Figure 4.3:

The probability distributions from Figure 4.2

plotted on a logarithmic scale. A multiplication register of 591

stages was simulated with a single electron input and total register

gains of 100, 1000 and 10000 (curves A, B and C respectively). Model 1

was used for the individual gain stages, where additional electrons

are selected from a Poisson distribution. Panel b) shows an

enlargement of one portion of the plot in panel

a). The curves in panel a) were well fitted with

exponential functions for the case of large numbers of output

electrons, and these fits have been extrapolated as dashed lines in

panel b).

|

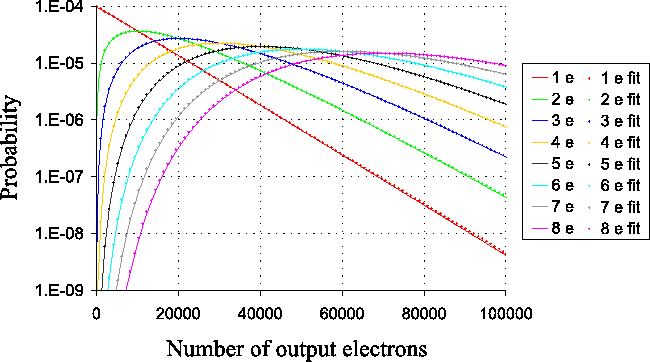

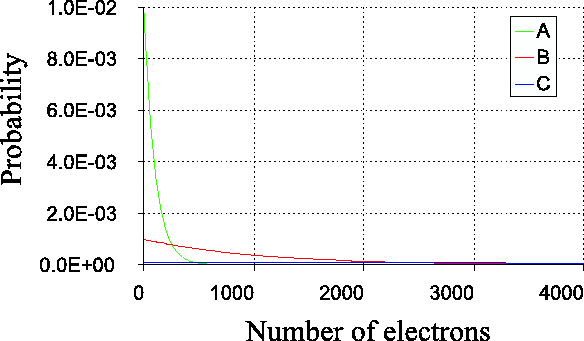

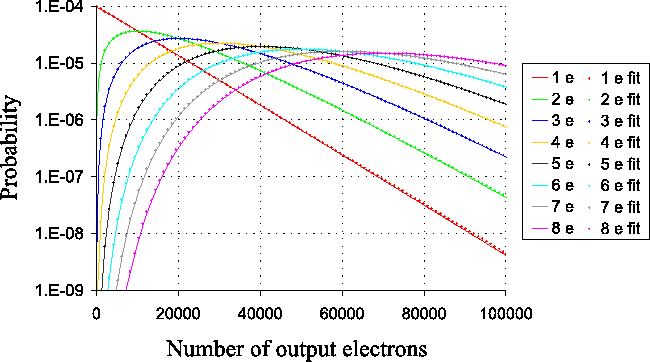

Figure 4.4 shows similar plots for a

stage register with overall gain

stage register with overall gain  with different numbers

of input electrons. The general shape of the curves was not strongly

dependent on the number of gain stages

with different numbers

of input electrons. The general shape of the curves was not strongly

dependent on the number of gain stages  as long as

as long as  was large.

was large.

Figure 4.4:

The probability distribution for the number of output electrons from a

multiplication register of  stages with different numbers of

input electrons. The discrete points on the graph show selected values

from the numerical fit described by

Equation 4.27, as discussed in the text.

stages with different numbers of

input electrons. The discrete points on the graph show selected values

from the numerical fit described by

Equation 4.27, as discussed in the text.

|

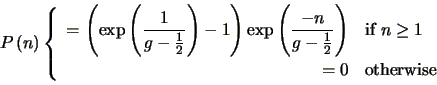

Based upon the exponential fits in

Figure 4.3, we can say that the

probability distributions for the number of output electrons produced

when one input electron enters an electron multiplying CCD with a

large number of gain stages can be approximated by the function:

|

(4.25) |

where  is an integer describing the number of output electrons and

is an integer describing the number of output electrons and

is the overall gain of the multiplication register.

is the overall gain of the multiplication register.

If we approximate Equation 4.25 as a

continuous function and convolve it with itself we get an

approximation for the probability distribution given two input

electrons:

|

(4.26) |

With further convolutions, and taking approximations for the case of

large gain  and a large number

and a large number  of input electrons, I obtained

the following model for the probability distribution for the output

electrons:

of input electrons, I obtained

the following model for the probability distribution for the output

electrons:

|

(4.27) |

where  is the number of output electrons. Individual data points

calculated using this equation are included in

Figure 4.4 alongside the appropriate

probability curves calculated numerically for model 1. The

approximation described by Equation 4.27

does not differ substantially from the numerically calculated curves

even for one or two input electrons (although slightly better

approximations for one and two input electrons are given by

Equations 4.25 and

4.26 respectively).

is the number of output electrons. Individual data points

calculated using this equation are included in

Figure 4.4 alongside the appropriate

probability curves calculated numerically for model 1. The

approximation described by Equation 4.27

does not differ substantially from the numerically calculated curves

even for one or two input electrons (although slightly better

approximations for one and two input electrons are given by

Equations 4.25 and

4.26 respectively).

Bob Tubbs

2003-11-14

![]() . This is highlighted in Figure 4.3a

where the curves are plotted on a logarithmic scale. The probability

curves appear as straight lines over a wide range of

. This is highlighted in Figure 4.3a

where the curves are plotted on a logarithmic scale. The probability

curves appear as straight lines over a wide range of ![]() in the

plot. For very large values of

in the

plot. For very large values of ![]() the probability reaches the

computational accuracy of the software corresponding to a value of

the probability reaches the

computational accuracy of the software corresponding to a value of

![]() , and beyond this point the probability calculations are

dominated by noise. Figure 4.3b shows an

expanded view of the probability distributions for small

, and beyond this point the probability calculations are

dominated by noise. Figure 4.3b shows an

expanded view of the probability distributions for small

![]() . Exponential curves were least-squares fitted to the probability

curves for the large

. Exponential curves were least-squares fitted to the probability

curves for the large ![]() region, and these are extrapolated as dashed

curves in this plot. For small values of

region, and these are extrapolated as dashed

curves in this plot. For small values of ![]() (

(![]() ) the

probability curve begins to fall very slightly below the best fit

exponential before dropping rapidly to zero for

) the

probability curve begins to fall very slightly below the best fit

exponential before dropping rapidly to zero for ![]() .

.

![]() stage register with overall gain

stage register with overall gain ![]() with different numbers

of input electrons. The general shape of the curves was not strongly

dependent on the number of gain stages

with different numbers

of input electrons. The general shape of the curves was not strongly

dependent on the number of gain stages ![]() as long as

as long as ![]() was large.

was large.

![]() and a large number

and a large number ![]() of input electrons, I obtained

the following model for the probability distribution for the output

electrons:

of input electrons, I obtained

the following model for the probability distribution for the output

electrons: