Next: Charge transfer efficiency problems Up: CCD measurements Previous: CCD measurements Contents

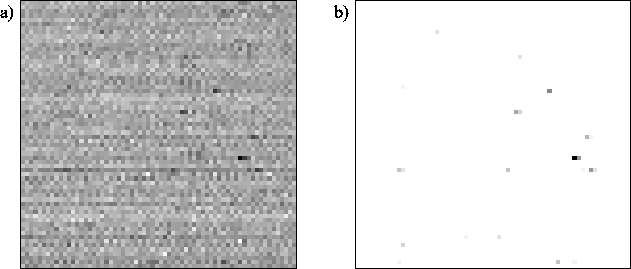

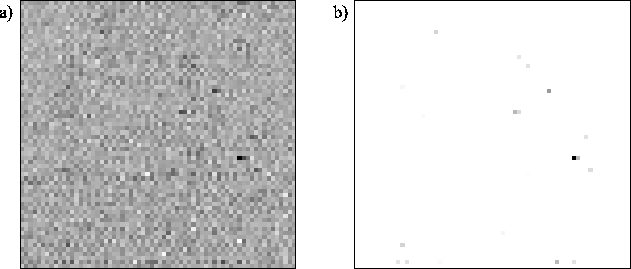

Figure 4.7 shows a small region of one short exposure taken while the camera was attached to the NOT on 2003 June 29. Long exposure imaging of the field displayed here showed that it did not contain any bright sources, so the detected flux is known to be much less than one photo-electron per pixel in this short exposure.

|

A small number of pixels in the short exposure show signal levels which are significantly higher than the typical noise in the image. It is likely that a photo-electron (or dark current electron) was generated in most of these pixels. The pixels with high signal levels found in several thousand short exposures such as this were found to be correlated with the locations of faint sources in the field, suggesting that they do indeed correspond to photon events.

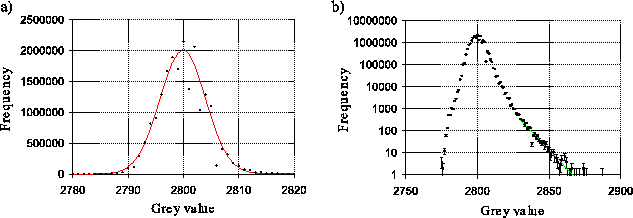

Figure 4.8 shows a histogram of the Digital Numbers (DNs)

output from the camera in ![]() exposures similar to the one shown in

Figure 4.7 (and including the exposure shown). The

peak of the histogram can be relatively well fit by a Gaussian

distribution, as shown in Figure 4.8a. The centre of this

Gaussian distribution corresponds to the mean signal when no photons

are detected in a pixel. The width of the Gaussian corresponds to the

RMS readout noise. A least-squares fit to the data gave a value of

exposures similar to the one shown in

Figure 4.7 (and including the exposure shown). The

peak of the histogram can be relatively well fit by a Gaussian

distribution, as shown in Figure 4.8a. The centre of this

Gaussian distribution corresponds to the mean signal when no photons

are detected in a pixel. The width of the Gaussian corresponds to the

RMS readout noise. A least-squares fit to the data gave a value of

![]()

![]() for the centre of the Gaussian. The fitted Gaussian

dropped to

for the centre of the Gaussian. The fitted Gaussian

dropped to ![]() of the peak value

of the peak value ![]()

![]() from the centre,

implying an RMS readout noise of

from the centre,

implying an RMS readout noise of ![]()

![]() . If each

. If each ![]() corresponds

to

corresponds

to ![]() electrons leaving the multiplication register, the RMS readout

noise

electrons leaving the multiplication register, the RMS readout

noise ![]() will be:

will be:

|

Figure 4.8b shows the same measurement data plotted on a

logarithmic scale. The frequency distribution is well fit by an

exponentially decaying function for high ![]() s (more than

s (more than ![]() from

the centre of the Gaussian) as would be expected given the presence of

photo-electrons in some of the pixels. The best fit exponential had a

decay constant of

from

the centre of the Gaussian) as would be expected given the presence of

photo-electrons in some of the pixels. The best fit exponential had a

decay constant of ![]() per

per ![]() . The gain of the multiplication

register can be calculated from

Equation 4.25 as:

. The gain of the multiplication

register can be calculated from

Equation 4.25 as:

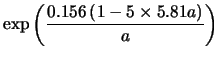

Applying Equation 4.29 to the parameters

given by Equations 4.30 and

4.31 allows us to calculate the efficiency ![]() for counting photo-electrons:

for counting photo-electrons:

|

(4.32) | ||

|

(4.33) |

For ![]() this gives an efficiency for photo-electron detection of:

this gives an efficiency for photo-electron detection of:

| (4.34) | |||

| (4.35) |

The reason for the poor photon counting performance is highlighted if

the RMS readout noise is expressed in terms of the mean input signal

provided by one photo-electron (i.e. if the RMS readout noise is

expressed in units of photo-electrons). This is achieved if

Equation 4.30 is divided by

Equation 4.31:

| (4.36) |

| (4.37) | |||

| (4.38) |

It should be noted that a readout noise of ![]() photo-electrons at

photo-electrons at

![]()

![]() pixel rates represents a very substantial improvement over

the read noise of

pixel rates represents a very substantial improvement over

the read noise of ![]() --

--![]() electrons for the camera used in the

observations described in Chapter 3. State-of-the-art

conventional CCDs can typically only achieve

electrons for the camera used in the

observations described in Chapter 3. State-of-the-art

conventional CCDs can typically only achieve ![]() --

--![]() electrons

read noise at these pixel rates (Jerram et al. , 2001).

electrons

read noise at these pixel rates (Jerram et al. , 2001).

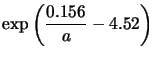

A large part of the RMS noise in the example short exposure shown in

Figure 4.7 is in the form of variations from one

horizontal row of the image to the next. If these fluctuations are

subtracted then the RMS noise is reduced. In order to do this it was

necessary to get a measure of the typical ![]() s in each individual row

of the image which was not strongly biased by the few pixels

containing photo-electrons. A histogram was made of the

s in each individual row

of the image which was not strongly biased by the few pixels

containing photo-electrons. A histogram was made of the ![]() s in each

row of the image. The lowest

s in each

row of the image. The lowest ![]() of

of ![]() s from the row were then

averaged to provide a value slightly lower than the mean for

s from the row were then

averaged to provide a value slightly lower than the mean for ![]() s in

the row, but not significantly biased by the small number of pixels

containing photo-electrons. This mean value was then subtracted from

all the pixels in the row. The image which resulted after this

procedure was applied to each row in Figure 4.7 is

shown in Figures 4.9a and

4.9b.

s in

the row, but not significantly biased by the small number of pixels

containing photo-electrons. This mean value was then subtracted from

all the pixels in the row. The image which resulted after this

procedure was applied to each row in Figure 4.7 is

shown in Figures 4.9a and

4.9b.

|

This process was applied to the full dataset of ![]() frames. The RMS

readout noise calculated from the histogram of the

frames. The RMS

readout noise calculated from the histogram of the ![]() s was reduced to

s was reduced to

![]() electrons, where

electrons, where ![]() is the number of electrons per

is the number of electrons per ![]() as

before. If the threshold for detection of a photo-electron is set at

as

before. If the threshold for detection of a photo-electron is set at

![]() times this RMS noise level, the efficiency of counting

photo-electrons comes to just over

times this RMS noise level, the efficiency of counting

photo-electrons comes to just over ![]() . Although this represents a

substantial improvement over the case where row to row fluctuations

are not subtracted, it will still give poorer signal-to-noise for

imaging than would be obtained by treating the measured

. Although this represents a

substantial improvement over the case where row to row fluctuations

are not subtracted, it will still give poorer signal-to-noise for

imaging than would be obtained by treating the measured ![]() s like an

analogue signal.

s like an

analogue signal.

These results appear to be typical of the data I have analysed from

the L3Vision camera at the NOT. It is clear that the photon counting

approach would not have been successful with this observational data,

so I will treat the ![]() s output from the camera in an analogue

fashion like the output from a conventional CCD camera in the

remainder of this thesis. On later nights of the observing run in 2003

a higher camera gain setting was used, but there has been insufficient

time to analyse that data for inclusion in this thesis.

s output from the camera in an analogue

fashion like the output from a conventional CCD camera in the

remainder of this thesis. On later nights of the observing run in 2003

a higher camera gain setting was used, but there has been insufficient

time to analyse that data for inclusion in this thesis.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14