A number of high resolution imaging techniques exist which involve

Fourier analysis of individual short exposure images taken at a large

telescope (see e.g. Roddier (1988)). Only those methods which

preserve some Fourier phase information from the source can be used to

produce true astronomical images, and the techniques which preserve

Fourier phase information require higher light levels than the Lucky Exposures and

shift-and-add methods (see e.g. Roddier (1988); Chelli (1987)). These

methods are thus limited to a smaller range of astronomical

targets. The bispectral analysis (speckle masking) method has often

been applied to data taken through masked apertures, where most of the

aperture is blocked off and light can only pass through a series of

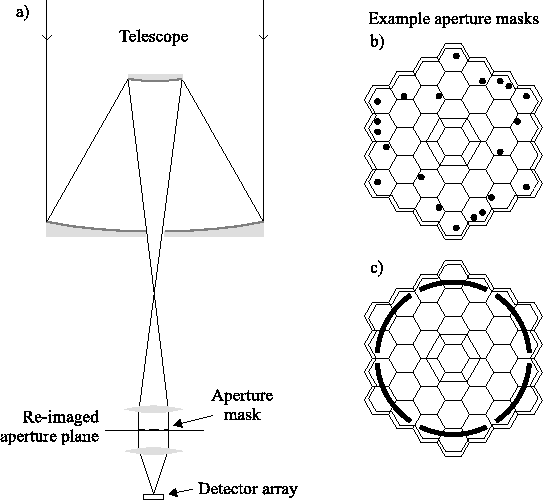

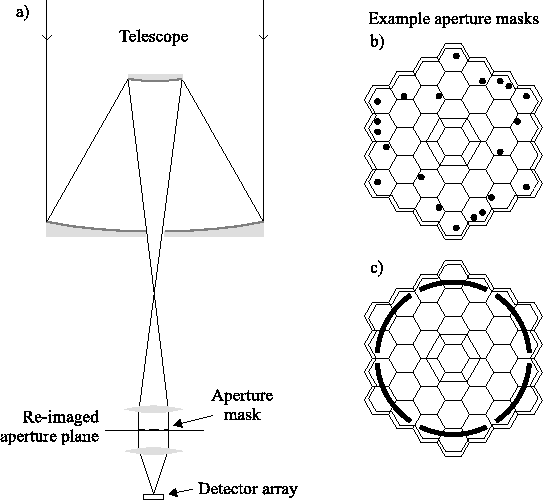

small holes (subapertures). For simplicity these aperture masks are

usually either placed in front of the secondary

(e.g. Tuthill et al. (2000)) or placed in a re-imaged aperture plane as

shown in Figure 1.6a

(e.g. Haniff et al. (1987); Young et al. (2000); Baldwin et al. (1986)). The masks are usually

categorised either as non-redundant or partially

redundant. Non-redundant masks consist of arrays of small holes where

no two pairs of holes have the same separation vector. Each pair of

holes provides a set of fringes at a unique spatial frequency in the

image plane. Partially redundant masks are usually designed to provide

a compromise between minimising the redundancy of spacings and

maximising both the throughput and the range of spatial frequencies

investigated (Haniff & Buscher, 1992; Haniff et al. , 1989). Figures 1.6b and

1.6c show examples of aperture masks used in front of the

secondary at the Keck telescope by Peter Tuthill and collaborators;

Figure 1.6b is a non-redundant mask while

Figure 1.6c is partially redundant. Although the

signal-to-noise at high light level can be improved with aperture

masks, the limiting magnitude cannot be significantly improved for

photon-noise limited detectors (see Buscher & Haniff (1993)).

Figure 1.6:

a) shows a simple experiment using an aperture mask in a re-imaged

aperture plane. b) and c) show diagrams of aperture masks which were

placed in front of the secondary mirror of the Keck telescope by Peter

Tuthill and collaborators. The solid black shapes represent the

subapertures (holes in the mask). A projection of the layout of the

Keck primary mirror segments is overlaid.

|

Bob Tubbs

2003-11-14