Next: Exposure selection from simulated Up: Lucky Exposures Previous: Numerical simulations Contents

| (2.18) |

|

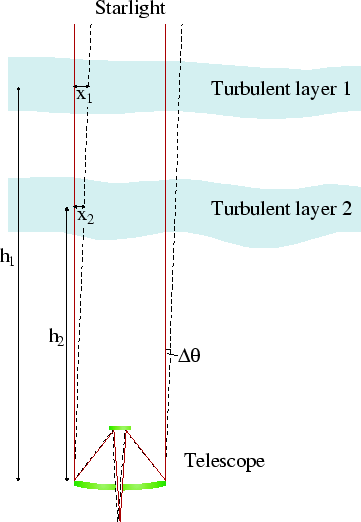

The angular separation at which the atmospheric perturbations applied to the light from the two stars becomes uncorrelated is called the isoplanatic angle. For a wind scatter model consisting of thin Taylor screens, the calculation of the isoplanatic angle is undertaken in an identical manner to the calculation of the timescale for decorrelation of the speckle pattern described above. The numerical simulations investigating the effect of relative motions of atmospheric layers on the image plane speckle pattern in Chapter 2.3.3 would be equally applicable to the study of isoplanatic angle, and the results can be used here directly. The similarity between the temporal properties and isoplanatic angle for wind-scatter models has been noted by a number of previous authors including Roddier et al. (1982a).

The calculation of the isoplanatic angle for atmospheres consisting of

a number of layers of Kolmogorov turbulence is described in

Roddier et al. (1982b), following a similar argument to that for

atmospheric coherence time calculations described in

Roddier et al. (1982a). The isoplanatic angle is inversely proportional to

the weighted scatter ![]() of the turbulent layer heights:

of the turbulent layer heights:

![\begin{displaymath}

\Delta h=\left [ \frac{ \int h^{2} C_{N}^{2} \left ( h \righ...

...^{2} \left ( h \right ) \mbox{d}h} \right )^{2} \right ]^{1/2}

\end{displaymath}](img273.png) |

(2.19) |

The decorrelation of the speckle pattern for a target with increasing

angular distance ![]() from a reference star is expected to follow

a similar relationship to that for the temporal decorrelation of a

speckle pattern (Equation 2.2). The

cross-correlation of the speckle patterns

from a reference star is expected to follow

a similar relationship to that for the temporal decorrelation of a

speckle pattern (Equation 2.2). The

cross-correlation of the speckle patterns

![]() should thus obey the relationship:

should thus obey the relationship:

I have not repeated the numerical simulations here for the case of

isoplanatism as the new simulations would be computationally identical

to those performed for the measurements of the timescale ![]() -

the only difference would be in the units used. The vertical axis in

Figure 2.5 is labelled

-

the only difference would be in the units used. The vertical axis in

Figure 2.5 is labelled ![]() , but it could

equally have been labelled isoplanatic angle

, but it could

equally have been labelled isoplanatic angle ![]() . The plot

would then correspond to the variation in isoplanatic angle as a

function of telescope diameter for two models of the atmosphere. The

model corresponding to curve A would be an atmosphere with a

single layer at an altitude of

. The plot

would then correspond to the variation in isoplanatic angle as a

function of telescope diameter for two models of the atmosphere. The

model corresponding to curve A would be an atmosphere with a

single layer at an altitude of ![]() , with the isoplanatic angle

, with the isoplanatic angle

![]() on the vertical axis plotted in units of

on the vertical axis plotted in units of

![]()

![]() . The model corresponding to curve

B would have two layers each with half the value of

. The model corresponding to curve

B would have two layers each with half the value of

![]() and at altitudes of

and at altitudes of ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

A number of different measures of the isoplanatic angle have been

suggested in the literature. In order to provide consistency with the

discussion of atmospheric timescales in

Chapters 2.2 and

2.3, I will take the isoplanatic angle

![]() for speckle imaging to be that at which the correlation

of the speckle pattern for two objects drops to

for speckle imaging to be that at which the correlation

of the speckle pattern for two objects drops to ![]() of the

value obtained near the reference star. For an atmosphere consisting

of Taylor screens, the value of

of the

value obtained near the reference star. For an atmosphere consisting

of Taylor screens, the value of ![]() will be dependent on the

relative motions of the Taylor screens with angle in same way as

will be dependent on the

relative motions of the Taylor screens with angle in same way as

![]() depends on the relative motions with time. For the model

described by Equation 2.20,

depends on the relative motions with time. For the model

described by Equation 2.20, ![]() will

be:

will

be:

| (2.21) |

Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994) suggest the isoplanatic angle for short exposure

imaging with the full aperture of the NOT will be significantly

larger than the isoplanatic angle expected for non-conjugate adaptive

optics (or for interferometric techniques involving small

apertures). This is due to the turbulent layers being distributed over

a narrow range of heights above the telescope. With non-conjugate

adaptive optics the isoplanatic angle is determined by the typical

height of the turbulence (whereas with large telescope apertures the

isoplanatic angle for speckle imaging techniques such as Lucky Exposures is

related to the scatter of different altitudes ![]() over which

the turbulence is distributed rather than the absolute height). In

calculating the isoplanatic angle for non-conjugate adaptive optics,

the deformable mirror (typically positioned in a re-imaged pupil

plane) can be treated like an additional layer of atmospheric

turbulence which cancels out the phase perturbations along one line of

sight, but contributes additional perturbation for objects

significantly off-axis.

over which

the turbulence is distributed rather than the absolute height). In

calculating the isoplanatic angle for non-conjugate adaptive optics,

the deformable mirror (typically positioned in a re-imaged pupil

plane) can be treated like an additional layer of atmospheric

turbulence which cancels out the phase perturbations along one line of

sight, but contributes additional perturbation for objects

significantly off-axis.

Measurements of the isoplanatic angle for speckle imaging at a number

of observatories have typical given values in the range ![]()

![]() to

to

![]()

![]() for observations at

for observations at ![]()

![]() wavelength (see

e.g. Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994); Roddier et al. (1982a)). The isoplanatic angle for speckle

observations is expected to be about

wavelength (see

e.g. Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994); Roddier et al. (1982a)). The isoplanatic angle for speckle

observations is expected to be about ![]() larger than that for

adaptive optics, based on measurements by Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994). The

isoplanatic angle for observations at I-band should be a further

factor of two larger due to the relationship between the coherence

length

larger than that for

adaptive optics, based on measurements by Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994). The

isoplanatic angle for observations at I-band should be a further

factor of two larger due to the relationship between the coherence

length ![]() and the wavelength

(Equation 2.9).

and the wavelength

(Equation 2.9).