Numerical simulations

A number of numerical simulations were undertaken to investigate the

temporal properties of Taylor screen models more

rigorously. Initially, two models were investigated, the first with a

single Taylor screen moving at a constant wind speed as discussed in

Chapter 2.3.2, the second having two equal Taylor

screens with slightly different wind speeds but the same wind

direction. The properties of the two models are summarised in

Table 2.1. The Taylor phase screens used had

Kolmogorov turbulence extending to an outer scale of  , with

no power on spatial frequencies larger than this. The size of the

outer scale was determined by the available computer memory. Both

simulations produced wavefront perturbations with the same coherence

length

, with

no power on spatial frequencies larger than this. The size of the

outer scale was determined by the available computer memory. Both

simulations produced wavefront perturbations with the same coherence

length  . Images from filled circular apertures with diameters

between

. Images from filled circular apertures with diameters

between  and

and  were generated at a large number of

discrete time points.

were generated at a large number of

discrete time points.

Table 2.1:

A brief summary of the two model atmospheres

investigated. The third column shows the scatter in the wind

velocities calculated using Equation 2.10.

|

|

Photometric measurements were made at a fixed point in the image plane

corresponding to each of the simulated apertures at each time point,

and the temporal autocorrelation of this data was

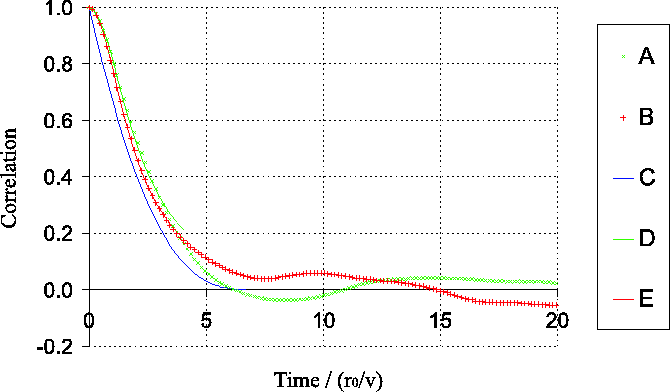

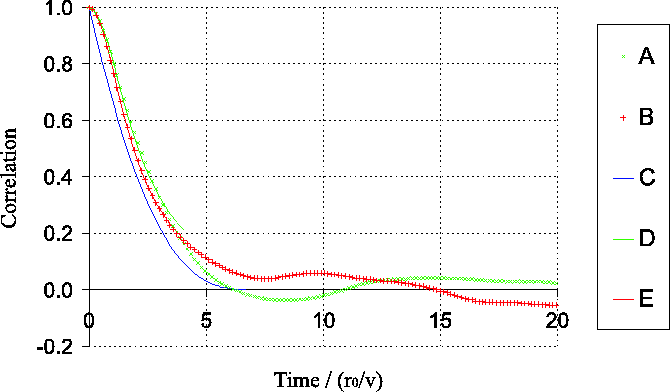

calculated. Figure 2.4 shows two example

autocorrelations for an aperture diameter of  . There is

relatively good agreement between the model of Aime et al. (1986)

(Equation 2.2) and the normalised

autocorrelation data from numerical simulations up to time differences

corresponding to the coherence timescale

. There is

relatively good agreement between the model of Aime et al. (1986)

(Equation 2.2) and the normalised

autocorrelation data from numerical simulations up to time differences

corresponding to the coherence timescale  . For larger time

differences Equation 2.2 tends quickly to

zero, while the simulation data usually drifted either side of zero

somewhat. This may be due to the limited timescale of the simulations

(a few hundred times

. For larger time

differences Equation 2.2 tends quickly to

zero, while the simulation data usually drifted either side of zero

somewhat. This may be due to the limited timescale of the simulations

(a few hundred times  , which is not long enough to average

very many realisations of the longer timescale changes in the speckle

pattern). Similar results were found for all of the aperture diameters

simulated, and the temporal power spectra were found to agree with the

model of Aime et al. (1986).

, which is not long enough to average

very many realisations of the longer timescale changes in the speckle

pattern). Similar results were found for all of the aperture diameters

simulated, and the temporal power spectra were found to agree with the

model of Aime et al. (1986).

Figure 2.4:

Two examples of the temporal autocorrelation curves generated from

numerical simulations (and used to produce

Figure 2.5). The curves have been normalised using the

method described in Chapter 2.2.1. A

shows the result for a single layer atmosphere and B for a

two-layer atmosphere (models 1 and 2 from

Table 2.1 respectively). C shows the

predicted decorrelation using the highly simplified model for a single

layer atmosphere described in

Appendix A. D and

E show least-squared fits of the form of

Equation 2.2 to the early parts of

curves A and B respectively.

|

The coherence

timescale  was then calculated from each simulation using

the method described in Chapter 2.2.1. A plot of

the variation of the coherence timescale with telescope aperture

diameter is shown in Figure 2.5.

was then calculated from each simulation using

the method described in Chapter 2.2.1. A plot of

the variation of the coherence timescale with telescope aperture

diameter is shown in Figure 2.5.

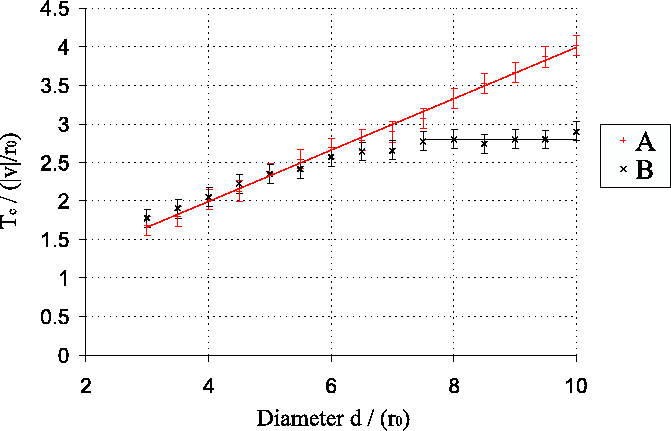

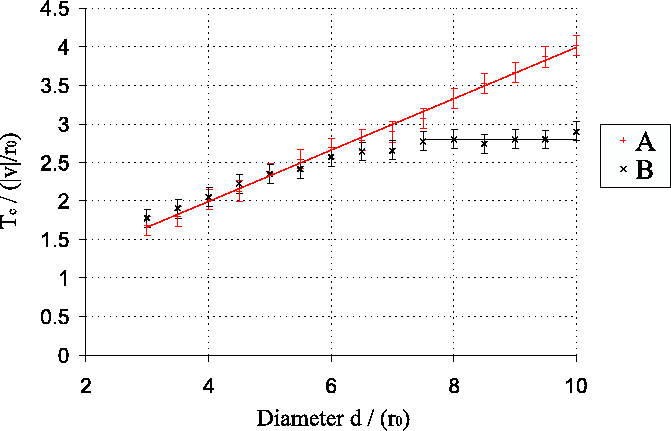

Figure 2.5:

Timescale  for a range of aperture diameters, for the two

atmospheric models. Curve A shows the result for a single

Taylor screen of frozen Kolmogorov turbulence. B is a similar

plot for the two layer atmosphere listed as model 2 in

Table 2.1. The error bars simply indicate the

standard error of the mean calculated from the scatter in results from

a number of repeated Monte Carlo simulations. Errors in the

measurements at different aperture diameters are partially correlated

as the same realisations of the model atmospheres were used for all

the aperture diameters shown. The red line is described by

Equation 2.14 and the black horizontal line is at

the value given in Equation 2.15.

for a range of aperture diameters, for the two

atmospheric models. Curve A shows the result for a single

Taylor screen of frozen Kolmogorov turbulence. B is a similar

plot for the two layer atmosphere listed as model 2 in

Table 2.1. The error bars simply indicate the

standard error of the mean calculated from the scatter in results from

a number of repeated Monte Carlo simulations. Errors in the

measurements at different aperture diameters are partially correlated

as the same realisations of the model atmospheres were used for all

the aperture diameters shown. The red line is described by

Equation 2.14 and the black horizontal line is at

the value given in Equation 2.15.

|

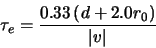

The red line in Figure 2.5 is a linear regression fit

to the measured timescale  for simulations with a single

Taylor screen. The equation for this best fit line is:

for simulations with a single

Taylor screen. The equation for this best fit line is:

|

(2.14) |

The timescale appears to depend approximately linearly on the aperture

diameter  , as predicted in

Appendix A. The value of

, as predicted in

Appendix A. The value of  was

found to be larger than predicted by my simplified model by a constant

amount

was

found to be larger than predicted by my simplified model by a constant

amount

. This is consistent

with a small region of the atmospheric layers extending

. This is consistent

with a small region of the atmospheric layers extending  into areas

into areas  and

and  in Figure A.3 being correlated

with the phase perturbations in area

in Figure A.3 being correlated

with the phase perturbations in area  . The same hypothesis would

explain why the measured temporal autocorrelations shown in

Figure 2.4 as curves A and B lie to

the right of the prediction corresponding to my simplified model

(curve C) over the left-hand part of the graph.

. The same hypothesis would

explain why the measured temporal autocorrelations shown in

Figure 2.4 as curves A and B lie to

the right of the prediction corresponding to my simplified model

(curve C) over the left-hand part of the graph.

For small aperture diameters, the simulations with a two-layer

atmosphere have very similar timescales to those with a single

atmospheric layer. However there is a knee at

, and at

diameters larger than this the timescale

, and at

diameters larger than this the timescale  appears to be

constant at:

appears to be

constant at:

|

(2.15) |

where

is the average wind velocity for the two

layers. It is of interest to compare this timescale with that

predicted by Equations 2.11 and

2.12. For this atmospheric model, the wind scatter

is the average wind velocity for the two

layers. It is of interest to compare this timescale with that

predicted by Equations 2.11 and

2.12. For this atmospheric model, the wind scatter

is equal to:

is equal to:

|

(2.16) |

The timescale  can be written in terms of

can be written in terms of  :

:

|

(2.17) |

This is larger than the timescales predicted by both

Equation 2.11 (from Roddier et al. (1982a)) and

Equation 2.12 (from Aime et al. (1986)). The result of

Aime et al. (1986) is within  of these simulations however

(remembering that the errors in the simulations are correlated for

different aperture diameters).

of these simulations however

(remembering that the errors in the simulations are correlated for

different aperture diameters).

Figure 2.5 implies that the timescale for changes in

the speckle pattern found at the focus of a well figured astronomical

telescope may increase somewhat with aperture diameter if the

atmospheric turbulence is moving with a common wind velocity. This would

not be the case if there is a substantial scatter in the wind

velocities, as the timescale saturates at a level close to that

predicted by Equation 2.12. Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994) found

that the scatter in the velocities of the turbulent layers above the

NOT is small enough that the timescale for speckle patterns using the

full aperture of the NOT should be twice the timescale which would be

found with small apertures, or that for standard adaptive optics

correction. This is consistent with measurements by

Saint-Jacques & Baldwin (2000) which indicated that a single wind velocity (or

narrow range of wind velocities) dominates above La Palma. This

contrasts with results at a number of other observatories

(e.g. Parry et al. (1979); Vernin & Roddier (1973); Caccia et al. (1987); Roddier et al. (1993)) where either strong

turbulence is found in several layers with differing wind velocities,

or there is little evidence for any bulk motion of the atmospheric

perturbations across the telescope aperture. Wilson (2003) also

found evidence for significant dispersion in the wind velocities above

the WHT on some nights.

Bob Tubbs

2003-11-14

![]() . There is

relatively good agreement between the model of Aime et al. (1986)

(Equation 2.2) and the normalised

autocorrelation data from numerical simulations up to time differences

corresponding to the coherence timescale

. There is

relatively good agreement between the model of Aime et al. (1986)

(Equation 2.2) and the normalised

autocorrelation data from numerical simulations up to time differences

corresponding to the coherence timescale ![]() . For larger time

differences Equation 2.2 tends quickly to

zero, while the simulation data usually drifted either side of zero

somewhat. This may be due to the limited timescale of the simulations

(a few hundred times

. For larger time

differences Equation 2.2 tends quickly to

zero, while the simulation data usually drifted either side of zero

somewhat. This may be due to the limited timescale of the simulations

(a few hundred times ![]() , which is not long enough to average

very many realisations of the longer timescale changes in the speckle

pattern). Similar results were found for all of the aperture diameters

simulated, and the temporal power spectra were found to agree with the

model of Aime et al. (1986).

, which is not long enough to average

very many realisations of the longer timescale changes in the speckle

pattern). Similar results were found for all of the aperture diameters

simulated, and the temporal power spectra were found to agree with the

model of Aime et al. (1986).

![]() was then calculated from each simulation using

the method described in Chapter 2.2.1. A plot of

the variation of the coherence timescale with telescope aperture

diameter is shown in Figure 2.5.

was then calculated from each simulation using

the method described in Chapter 2.2.1. A plot of

the variation of the coherence timescale with telescope aperture

diameter is shown in Figure 2.5.

![]() for simulations with a single

Taylor screen. The equation for this best fit line is:

for simulations with a single

Taylor screen. The equation for this best fit line is:

![]() , and at

diameters larger than this the timescale

, and at

diameters larger than this the timescale ![]() appears to be

constant at:

appears to be

constant at: