Next: Atmospheric models Up: Lucky Exposures Previous: The temporal power spectrum Contents

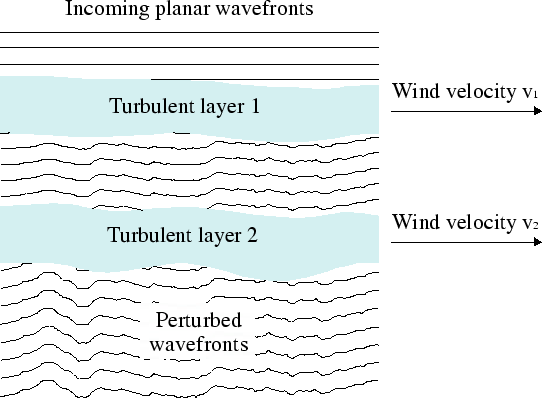

The layered model of atmospheric turbulence used for my simulations is supported by a number of experimental studies at Roque de los Muchachos observatory, La Palma (Vernin & Muñoz-Tuñón (1994); Wilson & Saunter (2003); Avila et al. (1997)); the model would also provide realistic results for many other good observatory sites.

|

Following the work of Tatarski (1961), the refractive index

fluctuations within a given layer in the simulations can be described

by their second order structure function:

| (2.4) |

The phase perturbations introduced into wavefronts by this layered

atmosphere can be described by the second order structure function for

the phase perturbations (Equation 1.3). This

function is dependent on the integral of

![]() along the light path

along the light path ![]() and the wavenumber

and the wavenumber ![]() as follows:

as follows:

(

![]() here is equivalent to

here is equivalent to

![]() in Tatarski (1961)).

in Tatarski (1961)).

Equation 2.6 can be more conveniently described in

terms of wavelength ![]() and the angular distance of the source

from the zenith

and the angular distance of the source

from the zenith ![]() :

:

Using Equations 1.4 and 2.7 we can

also write ![]() in terms of

in terms of

![]() :

:

Saint-Jacques & Baldwin (2000) undertook detailed atmospheric seeing measurements with the Joint Observatory Seeing Experiment (JOSE - Saint-Jacques et al. (1997); Wilson et al. (1999)) at the William Herschel Telescope, located at the same observatory as the NOT. The experimental setup consisted of an array of Shack-Hartmann sensors capable of measuring the wavefront tilt as a function of position and time in the aperture plane (see Figure 1.9). They found experimentally that the dominant atmospheric phase fluctuations at the William Herschel Telescope (WHT) are frequently associated with a single wind velocity, but also found evidence for gradual change in the phase perturbations applied to wavefronts as the perturbations progressed downwind. This can be explained either by turbulent boiling taking place within an atmospheric layer as it is blown past the telescope, or by the turbulence associated experimentally with one layer actually being distributed in several separate screens, with a narrow range of different wind velocities for the each of the screens (distributed about the measured mean wind velocity). This evolution of the turbulent structure for an atmospheric layer is consistent with the decorrelation with time of turbulent layers found by Caccia et al. (1987), although unlike Roque de los Muchachos observatory they found the typical atmosphere above Haute-Provence to have several such turbulent layers travelling at distinctly different wind velocities. Similar experiments were undertaken using binary stars at the WHT by Wilson (2003). The SLODAR technique (Wilson, 2002) was applied to these binary observations to obtain the heights of the turbulent layers as well as their wind velocities. Preliminary results provided by Wilson (2003) indicated that several turbulent layers with very different wind velocities were present on some of the nights. On at least one night, most of the turbulence was found at very low altitude above the WHT, and it is not necessarily certain that the same conditions would be present at the NOT further up the mountain.

For my numerical simulations I have ignored the possibility of turbulent boiling taking place within individual atmospheric layers because of the lack of a suitable mathematical model for the boiling process. Models which are free of boiling but which have multiple Taylor screens with a scatter of wind velocities describing each individual atmospheric layer can adequately fit existing experimental results, and these are the most widely used models for atmospheric simulations. This form of multiple Taylor screen model is usually known as a wind-scatter model.

Each of the atmospheric layers has a characteristic velocity for bulk

motion (![]() and

and ![]() for the two layers in

Figure 2.3) corresponding to the mean local wind

velocity at the altitude of the layer.

for the two layers in

Figure 2.3) corresponding to the mean local wind

velocity at the altitude of the layer.