Next: Observations Up: Experimental method Previous: Background Contents

In order to investigate the possible impact of any remaining aberrations, I undertook simulations with various different levels of mirror aberration. In the absence of direct measurements of the mirror shape after the adjustment to the actuators had been made I have suggested two models for the mirror aberrations as follows:

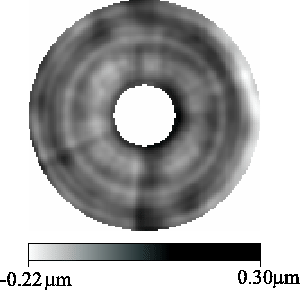

Model 1 represents a ``worst-case scenario'', with no improvement to the mirror aberrations after adjustment of the mirror supports. The mirror aberrations are taken directly from measurements of wavefront curvature made before the mirror actuators were adjusted (these measurements were provided by Sørensen (2002)). There is no defocus component in the model. The wavefront errors are shown as a function of position in the aperture plane in Figure 3.2.

Model 2 is identical to model 1 except that mirror aberrations on scales larger than the mean separation between adjacent mirror supports have been strongly suppressed. It is intended to represent a ``best-case scenario'', with near-optimal corrections to the mirror supports. The wavefront errors for model 2 are shown in Figure 3.3. It is understood that the residual wavefront errors at the NOT were small after the mirror actuators had been adjusted, hence the real shape of the primary mirror was probably similar to that shown in model 2.

|

Models 1 and 2 are intended to represent the two extremes of negligible improvement and near-optimal improvement. A third model investigated for purposes of comparison was that of a diffraction-limited mirror. The three models are summarised in Table 3.1

For each of the models the telescope PSF in the absence of the

atmosphere was generated using an FFT (as described in

Chapter 1.2.2). The PSF Strehl ratios obtained were

![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() for models 1, 2 and 3 respectively.

for models 1, 2 and 3 respectively.

For the numerical simulations based upon these models, the secondary

supports were ignored, and the telescope aperture was modelled as an

annulus with inner radius ![]() equal to that of the secondary

obscuration, and outer radius

equal to that of the secondary

obscuration, and outer radius ![]() determined by the radius of the

primary mirror (as shown in Figure 3.4). The

shape of the aperture used in the simulations can be described

mathematically in terms of the throughput

determined by the radius of the

primary mirror (as shown in Figure 3.4). The

shape of the aperture used in the simulations can be described

mathematically in terms of the throughput

![]() as a function of radius

as a function of radius ![]() (in the same way as for

Equation 1.7):

(in the same way as for

Equation 1.7):

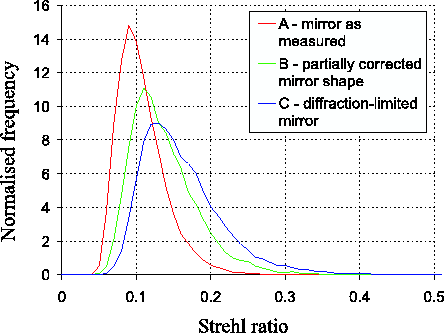

For each model, many realisations of atmospheric phase fluctuations

that had a Kolmogorov distribution with ![]() seven times smaller

than telescope diameter were calculated. These Kolmogorov

distributions had a large outer scale (approximately thirty times the

telescope diameter). The phase perturbations from the telescope mirror

for each model were added to the simulated atmospheric phase

distribution, and short exposure images were generated using the

aperture shape described by

Equation 3.1. The mirror aberrations in

models

seven times smaller

than telescope diameter were calculated. These Kolmogorov

distributions had a large outer scale (approximately thirty times the

telescope diameter). The phase perturbations from the telescope mirror

for each model were added to the simulated atmospheric phase

distribution, and short exposure images were generated using the

aperture shape described by

Equation 3.1. The mirror aberrations in

models ![]() and

and ![]() produce a reduction in the typical Strehl ratios

for the short exposure images when compared with the

diffraction-limited case. Histograms showing the frequency

distribution of Strehl ratios measured for the short exposures from

each of the models are shown in Figure 3.5.

produce a reduction in the typical Strehl ratios

for the short exposure images when compared with the

diffraction-limited case. Histograms showing the frequency

distribution of Strehl ratios measured for the short exposures from

each of the models are shown in Figure 3.5.

|

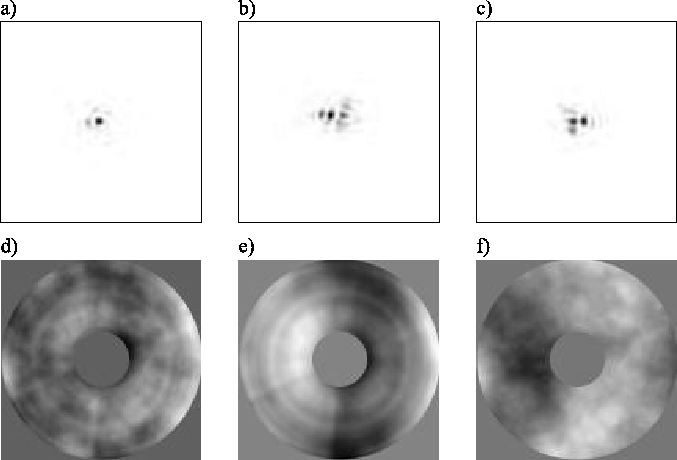

It is interesting to note that with model ![]() (the worst-case

scenario) some of the short exposures through the atmosphere have

higher Strehl ratios than would be obtained in the absence of the

atmosphere. In these exposures the atmospheric phase perturbations are

compensating for the errors in the figure of the telescope

mirror. This effect is even more noticeable under slightly better

astronomical seeing conditions. One example of an exposure with very

high Strehl ratio which appeared by chance in such a simulation is

shown in Figures 3.6a--f.

(the worst-case

scenario) some of the short exposures through the atmosphere have

higher Strehl ratios than would be obtained in the absence of the

atmosphere. In these exposures the atmospheric phase perturbations are

compensating for the errors in the figure of the telescope

mirror. This effect is even more noticeable under slightly better

astronomical seeing conditions. One example of an exposure with very

high Strehl ratio which appeared by chance in such a simulation is

shown in Figures 3.6a--f. ![]() for this

simulation was five times smaller than the telescope diameter.

Figure 3.6a shows the selected exposure with a

Strehl ratio of 0.32. The PSF of the telescope (in the absence of

atmospheric perturbations) is shown in

Figure 3.6b, with a Strehl ratio of

0.23. Figure 3.6c shows the PSF that would be

obtained through the same atmosphere using a diffraction-limited

telescope (i.e. the PSF for the atmospheric perturbations alone). The

shape of this PSF is almost a mirror-image of

Figure 3.6b, suggesting that the wavefront errors

from the atmosphere are approximately equal and opposite to the

aberrations introduced by the telescope. This is also apparent in

Figures 3.6d, 3.6e and

3.6f which show greyscale maps of the wavefront

error for the PSFs in Figures 3.6a,

3.6b and 3.6c respectively.

for this

simulation was five times smaller than the telescope diameter.

Figure 3.6a shows the selected exposure with a

Strehl ratio of 0.32. The PSF of the telescope (in the absence of

atmospheric perturbations) is shown in

Figure 3.6b, with a Strehl ratio of

0.23. Figure 3.6c shows the PSF that would be

obtained through the same atmosphere using a diffraction-limited

telescope (i.e. the PSF for the atmospheric perturbations alone). The

shape of this PSF is almost a mirror-image of

Figure 3.6b, suggesting that the wavefront errors

from the atmosphere are approximately equal and opposite to the

aberrations introduced by the telescope. This is also apparent in

Figures 3.6d, 3.6e and

3.6f which show greyscale maps of the wavefront

error for the PSFs in Figures 3.6a,

3.6b and 3.6c respectively.

|

The atmosphere is much less likely to correct those phase

perturbations which have small spatial scales across the telescope

mirror, because the Kolmogorov wavefront perturbations have very

little power on small spatial scales. The perturbations in model ![]() are restricted to small spatial scales so little correction is

expected, but the phase perturbations in the model are sufficiently

small in amplitude that they only have a small impact on the

distribution of the measured Strehl ratios, as shown in

Figure 3.5.

are restricted to small spatial scales so little correction is

expected, but the phase perturbations in the model are sufficiently

small in amplitude that they only have a small impact on the

distribution of the measured Strehl ratios, as shown in

Figure 3.5.

It is clear from the tails of the distributions in

Figure 3.5 that we can expect the best short

exposure images taken at the NOT to have reasonably high Strehl

ratios under good atmospheric seeing conditions. Even with model 1,

representing something of a worst-case scenario, Strehl ratios higher

than ![]() are expected

are expected ![]() of the time.

of the time.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14