Next: Strehl ratios obtained for zeta Bootis Up: Results with binary stars Previous: Data taken on zeta Bootis Contents

Some of the results from the ![]() Boötis data are summarised in

Figure 3.21.

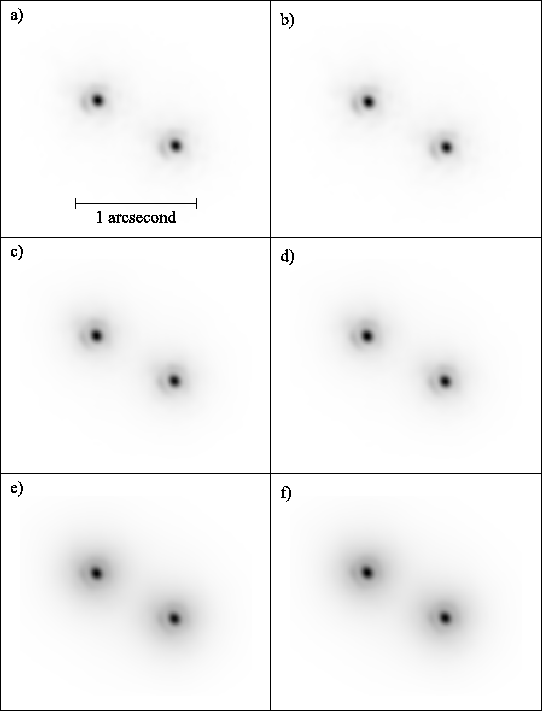

Figure 3.21a shows an image generated from

the short exposures have the highest

Boötis data are summarised in

Figure 3.21.

Figure 3.21a shows an image generated from

the short exposures have the highest ![]() % of Strehl ratios as

measured on the left-hand component of

% of Strehl ratios as

measured on the left-hand component of ![]() Boötis. The stellar

images appear almost diffraction limited, with the first Airy ring

clearly visible. The diffuse halo surrounding the stars is very faint

and barely visible in the image. Figure 3.21b

shows the result when the process is repeated using the right-hand

star as the reference for measuring Strehl ratio and the position of

the brightest speckle. Figures 3.21a and

3.21b are almost indistinguishable to the

eye, emphasising the high degree of isoplanatism and the good

signal-to-noise in the images. The Strehl ratio for the reference star

in each case is

Boötis. The stellar

images appear almost diffraction limited, with the first Airy ring

clearly visible. The diffuse halo surrounding the stars is very faint

and barely visible in the image. Figure 3.21b

shows the result when the process is repeated using the right-hand

star as the reference for measuring Strehl ratio and the position of

the brightest speckle. Figures 3.21a and

3.21b are almost indistinguishable to the

eye, emphasising the high degree of isoplanatism and the good

signal-to-noise in the images. The Strehl ratio for the reference star

in each case is ![]() .

.

|

Figures 3.21c and

3.21d show images generated in a similar way

but using the short exposures which have the highest ![]() of Strehl

ratios. A diffuse halo is clearly visible around both stars slightly

reducing the Strehl ratio for the reference star images to

of Strehl

ratios. A diffuse halo is clearly visible around both stars slightly

reducing the Strehl ratio for the reference star images to ![]() .

.

Figures 3.21e and

3.21f show images generated in a similar way

but using all of the short exposures regardless of Strehl ratio. The

diffuse halos are much more prominent around the stars reducing the

Strehl ratio for the reference star images to ![]() . These represent

the conventional shift-and-add images from the same data.

. These represent

the conventional shift-and-add images from the same data.

For all six images shown in Figure 3.21, the

Strehl ratio for the binary companion was found to be only

![]() as high as that of the reference star. This indicates a small

level of decorrelation between the shapes of the stellar images for

the two binary components as recorded on the detector. It is likely

that the decorrelation comes partially from noise sources such as

detector readout noise, photon shot noise, and in particular the

pixellation of the stellar image on the detector. Both the exposure

selection step and the image re-centring have a tendency to coherently

add the noise components in the image of the reference star to give an

artificially high Strehl ratio for this binary component. This effect

is described in detail by Nieto & Thouvenot (1991) for the photon-shot noise

component. The noise contribution is not expected to show strong

correlation between the separate binary components, so the Strehl

ratio for the binary companion should not be systematically affected

in this way.

as high as that of the reference star. This indicates a small

level of decorrelation between the shapes of the stellar images for

the two binary components as recorded on the detector. It is likely

that the decorrelation comes partially from noise sources such as

detector readout noise, photon shot noise, and in particular the

pixellation of the stellar image on the detector. Both the exposure

selection step and the image re-centring have a tendency to coherently

add the noise components in the image of the reference star to give an

artificially high Strehl ratio for this binary component. This effect

is described in detail by Nieto & Thouvenot (1991) for the photon-shot noise

component. The noise contribution is not expected to show strong

correlation between the separate binary components, so the Strehl

ratio for the binary companion should not be systematically affected

in this way.

It is clear from Figures 3.21a to

3.21f that the imaging PSF degrades

gradually as the fraction of exposures selected is increased. The

gradual nature of this change may be extremely useful in astronomical

programs as the performance of the Lucky Exposures method can be adjusted

according to the scientific needs. If an astronomical target is too

faint to give good signal to noise using only the best ![]() of

exposures, the astronomer can choose to use a larger fraction of

exposures at the expense of a small degradation in the image

quality. If the observational data are stored in a suitable manner,

the fraction of exposures selected can be adjusted after the

observations have been completed (during the data reduction) in order

to give the highest quality science results.

of

exposures, the astronomer can choose to use a larger fraction of

exposures at the expense of a small degradation in the image

quality. If the observational data are stored in a suitable manner,

the fraction of exposures selected can be adjusted after the

observations have been completed (during the data reduction) in order

to give the highest quality science results.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14