Next: Weighting exposures Up: Results with binary stars Previous: Strehl ratios obtained for zeta Bootis Contents

|

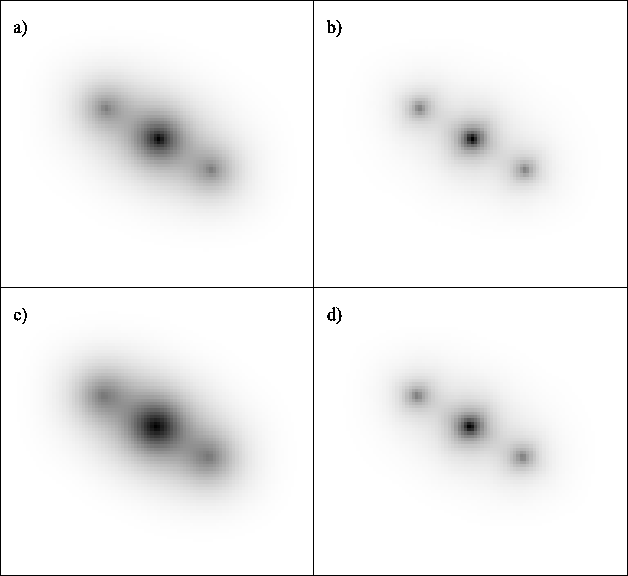

Figure 3.28a shows the summation of the autocorrelations

for all the short exposures used in the analysis. This image

essentially represents the method of Labeyrie (1970) as applied to

our data on ![]() Boötis. Figure 3.28b shows the

summation of the autocorrelations for only those exposures having the

highest

Boötis. Figure 3.28b shows the

summation of the autocorrelations for only those exposures having the

highest ![]() % of Strehl ratios. This autocorrelation has a much more

compact core and a fainter halo, indicating that the best

% of Strehl ratios. This autocorrelation has a much more

compact core and a fainter halo, indicating that the best ![]() % of

exposures preserve significantly more high spatial frequency

information.

% of

exposures preserve significantly more high spatial frequency

information.

It is now of interest to compare the autocorrelations of Figure 3.28a and 3.28b (generated directly from the raw data) with the autocorrelations obtained after the short exposures have been processed using either the conventional shift-and-add approach or using the Lucky Exposures method. Figure 3.28c shows the autocorrelation generated from the conventional shift-and-add image based on the same exposures as were used in Figure 3.28a. The shift-and-add process has produced a substantial reduction in the sharpness of the final autocorrelation, which indicates that the shift-and-add image itself is somewhat degraded in resolution. On the other hand, the autocorrelation of the shift-and-add image generated using the selected exposures (Figure 3.28d) is almost as sharp as that generated directly from the original exposures (Figure 3.28b). It is clear that with the Lucky Exposures method, one benefits not only from the higher resolution of the selected exposures themselves, but also from a substantial improvement in the performance of the shift-and-add process when it is applied to these high Strehl ratio exposures.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14