Next: Anisoplanatism Up: Results with binary stars Previous: Resolution and spatial frequency Contents

The short exposure images of ![]() Boötis in the first run were

first sorted in order of the Strehl ratio measured on the brighter

component. The exposures were then binned into groups of exposures

with similar Strehl ratios, each group containing

Boötis in the first run were

first sorted in order of the Strehl ratio measured on the brighter

component. The exposures were then binned into groups of exposures

with similar Strehl ratios, each group containing ![]() % of the total

exposures. The exposures in each group were then shifted and co-added,

reducing the dataset to

% of the total

exposures. The exposures in each group were then shifted and co-added,

reducing the dataset to ![]() images, each representing one of the

groups.

images, each representing one of the

groups.

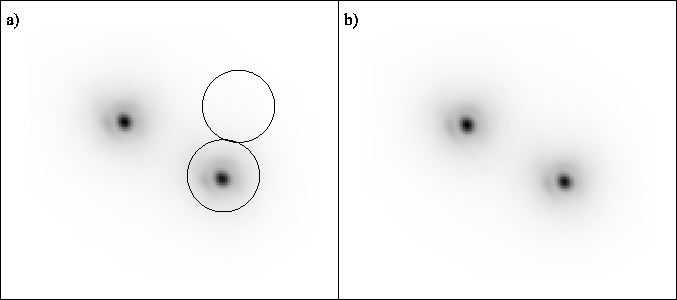

The signal-to-noise measurement described above was applied to these

![]() images using the b component of

images using the b component of ![]() Boötis (the a

component had been used as the reference star). The region around the

b component used for the ``signal'' measurements was limited to the

circle around the star shown in Figure 3.29a. A

circular flat-topped window which dropped smoothly to zero at the

edges (similar to a Hanning window) was used to extract a finite

region of the image data without introducing high frequency noise

components at the boundaries of the circle. A similar section of the

image away from the stars was used for noise measurements (shown by

the upper circle in the image). The range of spatial frequencies used

to represent

high resolution in the image was initially chosen (rather

arbitrarily) as those ranging between

Boötis (the a

component had been used as the reference star). The region around the

b component used for the ``signal'' measurements was limited to the

circle around the star shown in Figure 3.29a. A

circular flat-topped window which dropped smoothly to zero at the

edges (similar to a Hanning window) was used to extract a finite

region of the image data without introducing high frequency noise

components at the boundaries of the circle. A similar section of the

image away from the stars was used for noise measurements (shown by

the upper circle in the image). The range of spatial frequencies used

to represent

high resolution in the image was initially chosen (rather

arbitrarily) as those ranging between ![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() , and the image power spectrum was summed in

two dimensions over these spatial frequencies. The effect of varying

this range of spatial frequencies will be discussed later.

, and the image power spectrum was summed in

two dimensions over these spatial frequencies. The effect of varying

this range of spatial frequencies will be discussed later.

|

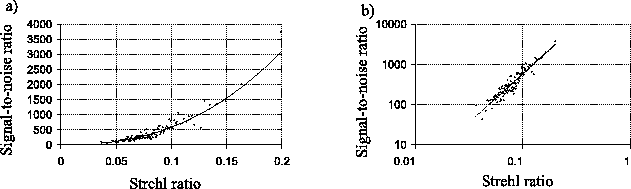

The signal-to-noise ratio ![]() for high spatial frequencies calculated

in this way is plotted against the Strehl ratio

for high spatial frequencies calculated

in this way is plotted against the Strehl ratio ![]() for the

reference star in the images in Figure 3.30a. Also

shown is the best fitting function of the form:

for the

reference star in the images in Figure 3.30a. Also

shown is the best fitting function of the form:

| (3.4) |

|

Now that we have a relationship between the Strehl ratio of the short

exposures and ![]() , our measure of the signal-to-noise ratio, we can

make a concerted effort to produce the image with the maximum

signal-to-noise ratio using the data on

, our measure of the signal-to-noise ratio, we can

make a concerted effort to produce the image with the maximum

signal-to-noise ratio using the data on ![]() Boötis. If the

individual exposures are treated as independent, uncorrelated

measurements, then the signal-to-noise ratio should be maximised if

all the exposures are selected, but the individual exposures are

weighted according to their Strehl ratios.

Boötis. If the

individual exposures are treated as independent, uncorrelated

measurements, then the signal-to-noise ratio should be maximised if

all the exposures are selected, but the individual exposures are

weighted according to their Strehl ratios.

The data from the first run on ![]() Boötis were processed in this

way, with the individual exposures weighted by a value

Boötis were processed in this

way, with the individual exposures weighted by a value ![]() proportional to our signal-to-noise estimate:

proportional to our signal-to-noise estimate:

| (3.5) |

If the signal-to-noise criteria ![]() used to determine the

signal-to-noise ratio for high resolution imaging is modified, and the

same analysis is followed through, then the Strehl ratio of the final

image from the weighted exposures approach will be different. A number

of different measures of signal-to-noise were tested, either utilising

different ranges of spatial frequencies, or weighted proportionately

with the image Strehl ratio. For all the weighting models tested, I

also generated images with similar Strehl ratios using the simple

exposure selection method without weighting. The images generated

using exposure selection always gave similar signal-to-noise ratios to

the images generated using exposure weighting. With faint reference

stars the accuracy of the Strehl ratio measurements is dependent on

the Strehl ratio itself, and the choice of optimum weighting function

becomes very complex. The complexity of the various weighting models,

their dependence on the numerous aspects of the observations which

affect the accuracy of Strehl ratio measurements, and the increased

computational requirements make this approach less favourable than

simple exposure selection. The analyses in the remainder of this

thesis will be restricted to exposure selection without weighting of

the exposures.

used to determine the

signal-to-noise ratio for high resolution imaging is modified, and the

same analysis is followed through, then the Strehl ratio of the final

image from the weighted exposures approach will be different. A number

of different measures of signal-to-noise were tested, either utilising

different ranges of spatial frequencies, or weighted proportionately

with the image Strehl ratio. For all the weighting models tested, I

also generated images with similar Strehl ratios using the simple

exposure selection method without weighting. The images generated

using exposure selection always gave similar signal-to-noise ratios to

the images generated using exposure weighting. With faint reference

stars the accuracy of the Strehl ratio measurements is dependent on

the Strehl ratio itself, and the choice of optimum weighting function

becomes very complex. The complexity of the various weighting models,

their dependence on the numerous aspects of the observations which

affect the accuracy of Strehl ratio measurements, and the increased

computational requirements make this approach less favourable than

simple exposure selection. The analyses in the remainder of this

thesis will be restricted to exposure selection without weighting of

the exposures.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14