Next: Performance of ground-based high Up: Short exposure optical imaging Previous: Example short exposure images Contents

It is useful at this stage to define a quantitive measure of image

quality. One approach is to compare the PSF measured through the

atmosphere with the diffraction-limited PSF expected in the absence

of atmospheric aberrations. The ratio of the peak intensity in the

PSF measured for an aberrated optical system to that expected for a

diffraction-limited system is widely known as the Strehl ratio,

after the work of Strehl (1895,1902). In this case we treat the

atmospheric perturbations as the optical aberration, with the

telescope itself assumed to be aberration-free. In order to ensure

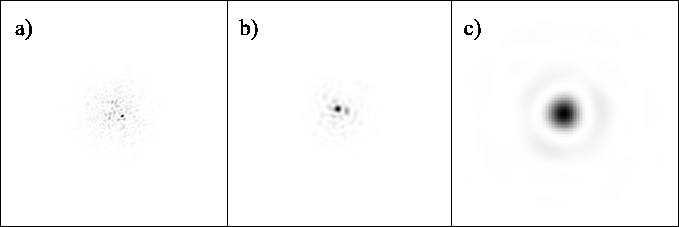

that the images shown in Figure 1.3 were

``typical'', several thousand random realisations of each PSF were

generated, and the three with the median Strehl ratios were chosen for

the figure. The Strehl ratios of the exposures picked were ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() for Figures 1.3a,

1.3b and 1.3c respectively.

for Figures 1.3a,

1.3b and 1.3c respectively.

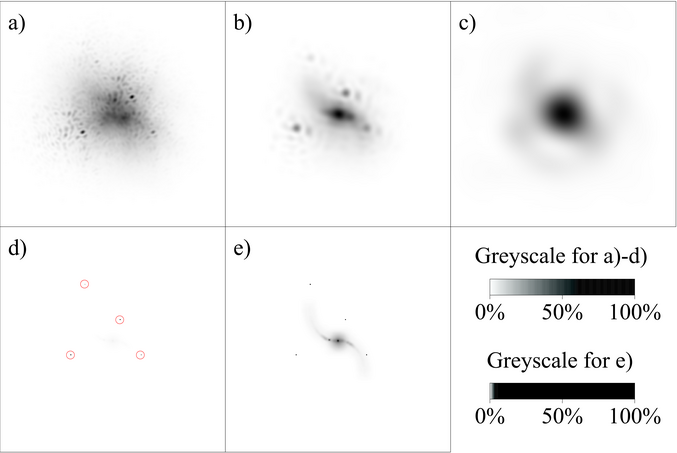

As the atmospheric fluctuations are random, one would occasionally expect these fluctuations to be arranged in such a way as to produce a diffraction-limited PSF, and hence good quality image. Fried (1978) coined the phrase ``Lucky Exposures'' to describe high quality short exposures which occur in such a fortuitous way. A perfectly diffraction-limited PSF will be extremely unlikely, but it is of interest to assess how good an image one would expect to occur relatively often during an observing run. If the speckle patterns change on timescales of a few milliseconds, and we are willing to wait a few seconds for our good image, then we can wait for a one-in-a-thousand Lucky Exposures. From several thousand random realisations I selected the PSFs with the highest 0.1% of Strehl ratios. Figures 1.4a--c show examples of these PSFs with the same atmospheric conditions and telescope diameters as were used for Figure 1.3a--c respectively.

|

Figure 1.4b is dominated by a single speckle which contains a significant fraction of the total intensity in the image. If we take this speckle to be similar in size and shape to a diffraction-limited PSF, then the measured Strehl ratio of 43% implies that the speckle contains about 43% of the total light intensity. The remaining light is found in a large number of much fainter speckles. The surface brightness from these background speckles is relatively small and should not result in a very noisy image.

Figure 1.4c is very similar to the typical exposure shown in Figure 1.3c. With this aperture size the PSF of a lucky exposure shows little improvement over that for a typical exposure. The broad core of the PSF is dominated by diffraction through the small aperture, giving very poor angular resolution.

Fried (1978) suggested that for an aperture of diameter ![]() or

or

![]() , roughly 0.1% of the short exposures should be of very good

quality (with the RMS variation in wavefront phase over the aperture

less than one radian). This is borne out by the compact core and high

Strehl ratio for the PSF shown in Figure 1.4b, which

should mean that this case provides better high-resolution imaging

performance than Figures 1.4a and

1.4c.

, roughly 0.1% of the short exposures should be of very good

quality (with the RMS variation in wavefront phase over the aperture

less than one radian). This is borne out by the compact core and high

Strehl ratio for the PSF shown in Figure 1.4b, which

should mean that this case provides better high-resolution imaging

performance than Figures 1.4a and

1.4c.

In order to compare the imaging performance of the PSFs qualitatively, each of the PSFs in Figures 1.4a--c was convolved with a simulated astronomical image; the results are shown in Figures 1.5a--c respectively. For comparison, an image on the same scale was generated using an ideal PSF (a delta-function), and this is displayed in Figures 1.5d and 1.5e. Both the galaxy-like structure and the point sources are clearly evident in Figure 1.5b, whereas these structures are much more difficult to make out in Figures 1.5a and 1.5c.

|

Determination of the instantaneous PSF from short exposure images of a reference star, and the use of such PSF measurements to select the exposures with the highest Strehl ratio and to then re-centre and co-add these exposures forms the basis for most of the work described in this thesis. I will refer to this method as the Lucky Exposures technique. A number of other authors have published results using very similar methods, particularly for solar and planetary observations. Observations of fainter astronomical targets have typically used exposure times which are too long to freeze the atmosphere, but these have often produced valuable astronomical science results nevertheless (Nieto & Thouvenot, 1991; Lelievre et al. , 1988; Nieto et al. , 1987,1988; Crampton et al. , 1989; Nieto et al. , 1990). Dramatic improvements in CCD technology have allowed recent observations to be performed at much higher frame rates (Dantowitz et al. , 2000; Davis & North, 2001; Baldwin et al. , 2001), providing new insights into the characteristics of the atmosphere, and demonstrating the potential of high frame-rate imaging using low noise detectors.

To help provide some background material in the field of high resolution imaging, I will now introduce some alternative methods for high resolution imaging. This will hopefully clarify the advantages and disadvantages of Lucky Exposures.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14