Next: Exposure selection Up: Short exposure optical imaging Previous: The outer and inner Contents

The effect of the finite aperture size of the telescope can be

simulated by setting the wavefront amplitude to zero everywhere in the

aperture plane except where the light path to the primary mirror is

unobstructed. This can be achieved most easily by defining a function

![]() which describes the effect of the telescope

aperture plane coverage on the wavefronts in the same way that the

effect of the atmosphere is described by

which describes the effect of the telescope

aperture plane coverage on the wavefronts in the same way that the

effect of the atmosphere is described by

![]() . The value of

. The value of

![]() will be zero beyond the edge of the primary

mirror and anywhere the primary is obstructed, but unity

elsewhere. For the simple case of a circular primary mirror of radius

will be zero beyond the edge of the primary

mirror and anywhere the primary is obstructed, but unity

elsewhere. For the simple case of a circular primary mirror of radius

![]() without secondary obstruction:

without secondary obstruction:

Phase perturbations introduced into the wavefronts by

aberrations in the telescope can be described by a function

![]() in similar way, resulting in wave-function

in similar way, resulting in wave-function

![]() given by:

given by:

I will begin with the simple case of a telescope which is free of

optical aberrations observing in a narrow wavelength band. The

perturbed wave-function reaching the telescope aperture for this case

is given by setting

![]() in

Equation 1.8. Combined with

Equation 1.6 this gives:

in

Equation 1.8. Combined with

Equation 1.6 this gives:

For the simulations a long-period pseudo-random number generator was

used to produce two-dimensional arrays containing discrete values of

![]() , having the second order structure

function defined by Equation 1.4, using a standard

algorithm provided by Keen (1999). The time evolution of

, having the second order structure

function defined by Equation 1.4, using a standard

algorithm provided by Keen (1999). The time evolution of

![]() was ignored, as I was interested in the

instantaneous imaging performance (the case for short

exposures). Arrays of

was ignored, as I was interested in the

instantaneous imaging performance (the case for short

exposures). Arrays of

![]() were then

generated corresponding to the wave-function provided by a distant

point source after passing through the atmospheric phase perturbations

and the telescope aperture using Equation

1.9. These arrays were Fourier transformed

using a standard Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) routine to provide

images of the point source as seen through the atmosphere and

telescope. The image of a point source through an optical system is

called the point-spread-function (PSF) of the optical system. For our simple optical

arrangement with phase perturbations very close to the aperture plane,

the response of the system to extended sources of incoherent light is

simply the convolution of the PSF with a perfect image of the

extended source.

were then

generated corresponding to the wave-function provided by a distant

point source after passing through the atmospheric phase perturbations

and the telescope aperture using Equation

1.9. These arrays were Fourier transformed

using a standard Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) routine to provide

images of the point source as seen through the atmosphere and

telescope. The image of a point source through an optical system is

called the point-spread-function (PSF) of the optical system. For our simple optical

arrangement with phase perturbations very close to the aperture plane,

the response of the system to extended sources of incoherent light is

simply the convolution of the PSF with a perfect image of the

extended source.

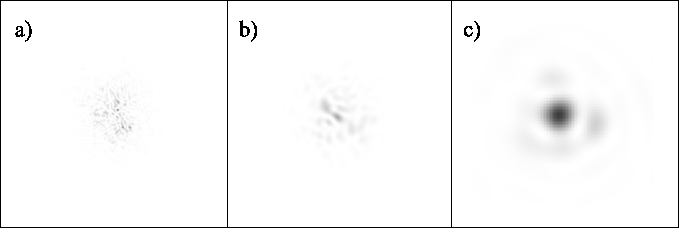

Figure 1.3 shows simulated PSFs for three

atmospheric realisations having the same ![]() and image scales but

with different telescope diameters. There are two distinct regimes for

the cases of large (diameter

and image scales but

with different telescope diameters. There are two distinct regimes for

the cases of large (diameter ![]() ) and small (

) and small (![]() )

telescopes. Figure 1.3a is a typical PSF from a

telescope of diameter

)

telescopes. Figure 1.3a is a typical PSF from a

telescope of diameter ![]() . The image is broken into a large

number of speckles, which are randomly distributed over a circular

region of the image with angular diameter

. The image is broken into a large

number of speckles, which are randomly distributed over a circular

region of the image with angular diameter

![]() , where

, where ![]() represents the

wavelength. With the slightly smaller aperture shown in Figure

1.3b the individual speckles are larger - this is

because the typical angular diameter for such speckles is

represents the

wavelength. With the slightly smaller aperture shown in Figure

1.3b the individual speckles are larger - this is

because the typical angular diameter for such speckles is

![]() , equal to the diameter of the PSF in the

absence of atmospheric phase perturbations for a telescope of the same

diameter

, equal to the diameter of the PSF in the

absence of atmospheric phase perturbations for a telescope of the same

diameter ![]() (i.e. a diffraction-limited PSF). For the small

aperture size shown in Figure 1.3c the shape of

the instantaneous PSF deviates little from the diffraction-limited

PSF given by a telescope of this diameter. The first Airy ring is

partially visible around the central peak.

(i.e. a diffraction-limited PSF). For the small

aperture size shown in Figure 1.3c the shape of

the instantaneous PSF deviates little from the diffraction-limited

PSF given by a telescope of this diameter. The first Airy ring is

partially visible around the central peak.

|

Real astronomical images of small fields obtained through the atmosphere will correspond to an image of the sky brightness distribution convolved with the PSF for the telescope and atmosphere. The perturbations introduced by the atmosphere change on timescales of a few milliseconds (known as the atmospheric coherence time). If the exposure time for imaging is shorter than the atmospheric coherence time, and the telescope is free of optical aberrations, then Figures 1.3a--c will be representative of the typical PSFs observed. The random distribution of speckles found in the short exposure PSFs of Figures 1.3a and 1.3b will have the effect of introducing random noise at high spatial frequencies into the images, making individual short exposures such as these of little direct use for high resolution astronomy. Figure 1.3c is dominated by a relatively uniform bright core, and as such will provide images with relatively high signal-to-noise. Unfortunately the broad nature of the PSF core severely limits the image resolution which can be obtained with such a small aperture.

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14