Next: Sky coverage Up: Results Previous: Assessment of image quality Contents

|

|

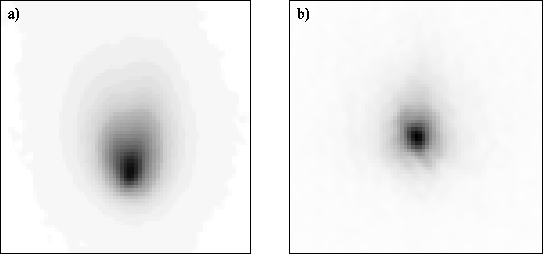

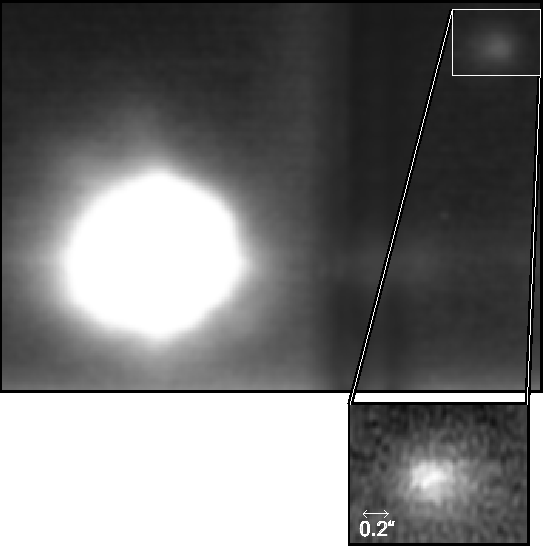

The dynamic range of Lucky Exposures is highlighted in a more quantative manner by

Figure 5.27. This data on Gliese 569 was taken at

a frame rate of ![]()

![]() on 2002 July 25 (as listed in

Table 5.3). At the

on 2002 July 25 (as listed in

Table 5.3). At the ![]()

![]() observing wavelength the

magnitude difference is

observing wavelength the

magnitude difference is ![]() , and yet the faint companion is easily

detected with little light contamination from the primary

, and yet the faint companion is easily

detected with little light contamination from the primary ![]()

![]() away. The data were taken through high Saharan dust extinction, and

there is insufficient signal-to-noise to separate the binary

components.

away. The data were taken through high Saharan dust extinction, and

there is insufficient signal-to-noise to separate the binary

components.

|

Bob Tubbs 2003-11-14